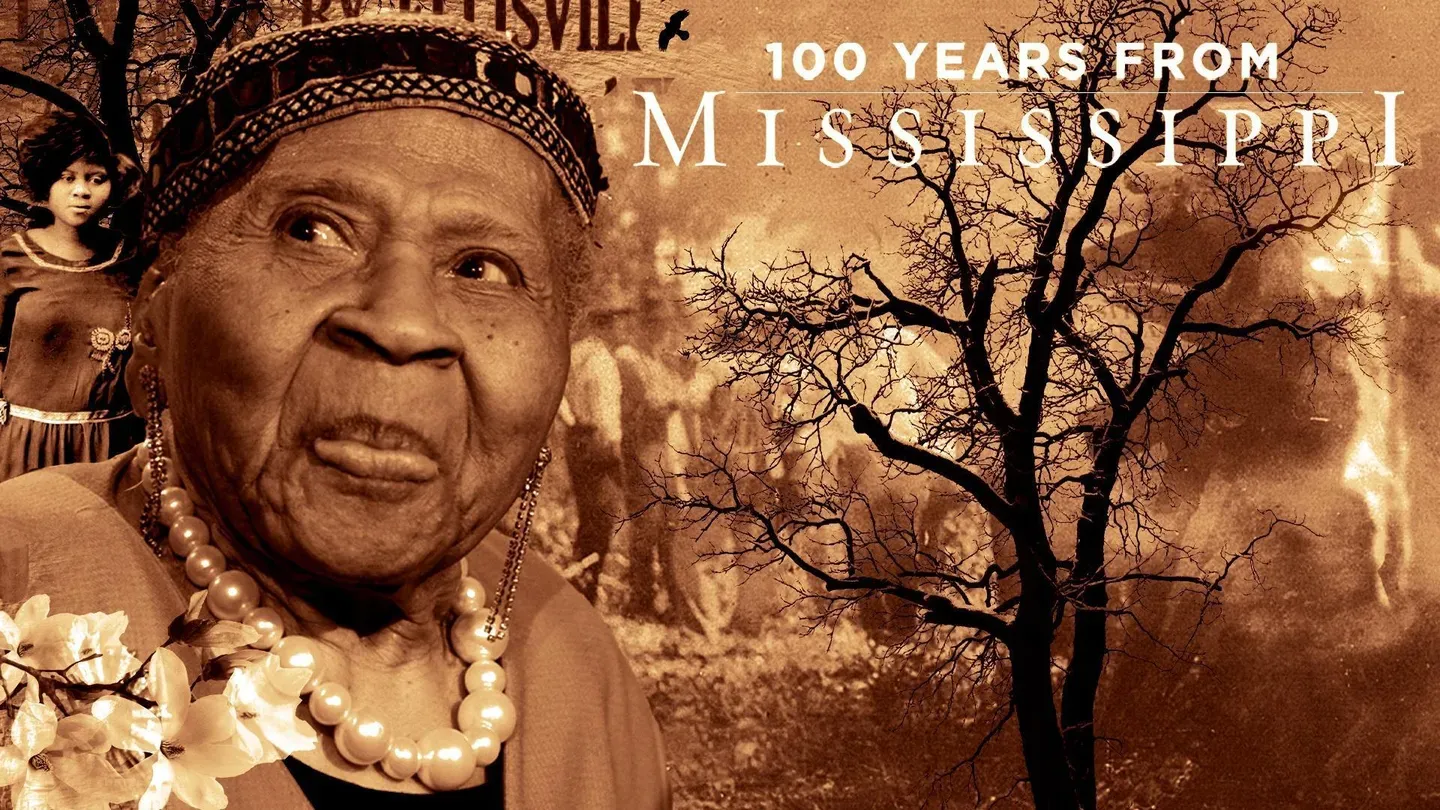

100 Years From Mississippi

100 Years From Mississippi

Special | 57m 50sVideo has Closed Captions

Mamie Lang Kirkland left Mississippi to escape racial violence and did not return for a ce

100 YEARS FROM MISSISSIPPI profiles the life of Mamie Lang Kirkland, who left Mississippi at seven years old to escape racial violence and would not return to the state until a century later.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

100 Years From Mississippi is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

100 Years From Mississippi

100 Years From Mississippi

Special | 57m 50sVideo has Closed Captions

100 YEARS FROM MISSISSIPPI profiles the life of Mamie Lang Kirkland, who left Mississippi at seven years old to escape racial violence and would not return to the state until a century later.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch 100 Years From Mississippi

100 Years From Mississippi is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

announcer: Funding for "100 Years From Mississippi" was provided by: The Angell Foundation, Josephine Ramirez & The James Irvine Foundation Staff Matching Gifts Program, Julie Mount Donor Advised Fund, Paul & Nicole Mones, Mamie Kirkland, Barry Shabaka Henley & Paulina Sahagun, Patty Hirota-Cohen & Lewis Cohen, Ellie Kanner, and Kat Taylor.

(mid-tempo upbeat string music) (mid-tempo upbeat string music) Mamie: What have I seen?

A whole lot.

It's been 110 years.

There have been two World Wars, the atomic bomb, the Depression, they almost starved us to death.

I lived through 20 Presidents.

I thought Hoover was the worst in my time, but that man with the funny hair takes the cake.

God blessed me with a good husband for 35 years, three months and 16 days.

I have seen a lot of beautiful things.

I mean, beautiful things.

(crowd chanting) -: Now we are grappling with basic class.

Mamie: I have seen a lot ugly things too.

The race riots, people being burned to death, Lord help us.

And people being lynched, and some of it has never changed.

It has not stopped.

(crowd yelling) Crowd: Hands up don't shoot, hands up don't shoot.

Mamie: It's life though, you have to take it.

I am grateful for all of it.

After all of that, I thank my God for my life.

It's a lot to go through, it's a lot to tell.

(Mamie laughing) Photographer: Okay, one, two three, Mamie.

Crowd: Mamie.

Photographer: Thumbs up.

(crowd cheering) Mamie: I wanna thank everybody for coming to spend some time with the young lady.

Guest: Young stuff, tenderoni.

(crowd laughing) -: And then the second, I want this to go to everybody.

Don't rush your life away.

Live it away, for the Lord.

(crowd cheering) September of this year.

-: September.

Aaron: Yeah, yeah, September third.

-: I will be 110, isn't that wonderful?

-: That's amazing.

-: It's a blessing.

-: That's a blessing.

-: It's amazing.

♪ When I wake up ♪ ♪ In the morning ♪ ♪ Drinking coffee on my balcony ♪ ♪ Trees are dancing ♪ ♪ Through the whistle of the wind ♪ ♪ Lord I'm thankful for everything ♪ ♪ When it's dark, light my way ♪ ♪ Bless my heart, Lord, bless my day ♪ ♪ I'm here, Lord, I'm thankful for everything ♪ ♪ Lord, I'm thankful ♪ Bryan Stevenson: Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in honoring Ms. Mamie Lang Kirkland.

♪ For everything ♪♪ (soft pensive music) Tarabu: When my mother was born in Ellisville, Mississippi in 1908, it had only been 43 years since slavery had been abolished.

She was part of the first migration of six million African Americans who fled the deep South.

(water rushing) Mamie lived in Buffalo, New York, for 95 years, since 1924.

But the winters became harder on her with age, so about 20 years ago my mother became a snow bird when my wife, Nobuko, and I started bringing her out to California to spend the winters with us until Buffalo began to thaw.

Come on now, you gotta finish your walk.

I'm your personal trainer.

I got to whip you in shape.

-: (laughing) I better stay in shape if I want to keep going.

Tarabu: After this we're gonna do 50 pushups.

Over the years, we've heard a century's worth of her stories over bowls of ice cream, and cups of coffee.

But when we decided to make this film, everything changed for both of us.

So you started selling Avon in 1963?

Mamie: Yeah, that was my first job.

(doorbell ringing) Announcer: Avon calling.

Mamie: I walked everywhere, I mean long walks.

But I had so many good customers.

A lot of my people didn't want me to leave.

And I'd talk to them, you know, I'd counsel them.

They getting ready to break up, or things like that, you know.

And I'd tell them, I'd say, "Just hold on, don't give up."

Tarabu: So how are you managing now, that everything's on the computer?

Mamie: I write them on a piece of paper and send them in.

Tarabu: You ever think you'd wanna learn a computer so you-- Mamie: No, no.

I went this long without a computer, let me do it the old-fashioned way.

Never wanted a microwave until Greg brought it in the house, and I didn't know what he was bringing.

Tarabu: And now do you like it?

Mamie: I love it.

(both laughing) I'm just old-fashioned, I'll always be like that.

I'd be just still riding the horse.

Tarabu: Well you know some places, they don't allow horses on the street anymore.

Mamie: I know they don't, but I'm the horse.

(laughing) I was born in Ellisville, Mississippi, September 3rd, 1908.

My father was a minister, and my mother was a housewife.

My grandfather was a Choctaw Indian.

My grandmother was a doctor/midwife.

They were all born in Mississippi.

But the house was a cute little house with a peach tree in the back.

And my mother she had it, oh, she was very clean and neat.

I can remember the house that was across the street.

Dirt roads, I'm looking at 'em now.

I had four sisters and one brother.

My grandmother delivered all of us.

They used to pick fights, my sister and them.

And then my father would find out, and I, I couldn't tell a lie.

"Who started the fight?"

And I'd say, "We did," and they got mad with me, you know, 'cause I told the truth.

(laughing) And all of us would get a whooping.

(laughing) It was a small life in Mississippi.

Tarabu: So you got sick when you were four or five years old?

Mamie: Five years old when I went to heaven.

I was so sick, I had the typhoid malaria fever, and they couldn't bring the fever down.

So the doctor came and he said, "Reverend Lang, "there's nothing I can do."

He give me up, I died, now this is true.

I mean, I went to heaven.

It was so beautiful up there.

The sky looked so pretty, all colors, shaped like rainbows.

And my grandmother being a midwife/doctor she said, "Wait, give me a chance."

She had one of these big aprons.

She got some herbs, she came back, she made some kinda tea.

I woke up, and when I woke up, I couldn't believe it, and they were all praying, my grandmother, and them was by the bed just praying and thanking God.

She was a midwife/doctor and a good one, and I can see her now getting on that horse late at night with the big cape on, riding to go get the babies.

And she, through God's help, the cause of me being here today.

And then after they started calling me gold baby.

Said 'cause I was a miracle child.

(laughing) (gentle soothing music) Narrator: "So since I'm still here living, "I guess I will live on.

"I coulda died for love, but for living I was born.

"Though you may hear me holler, and you may see me cry, "I'll be dogged sweet baby, if you gonna see me die."

Bryan Stevenson: Well the thing about Miss Kirkland's story is that it's so extraordinary to meet a survivor of the kind of threat and menace that she and her family faced, who kept that story close.

When I learned about her story, of course was just desperate to meet her, but it doesn't prepare you for the strength of her spirit and the depth of her conviction to bear witness to this history.

-: We've been trying to challenge racial bias in the criminal justice system for 30 years.

Our building is the site of a former slave warehouse, and these enslaved people would be held there, and then taken 100 yards up the street where they would be sold at the auction site.

I mean, as people who have represented folks on death row, having fought against the death penalty, and seen people executed not because of their crime, but because of their race and their poverty, there is this relationship between our contemporary work on the death penalty and lynching.

(slow somber music) (bomb bursting) Narrator: "I cannot conceive of a Negro "native to this country, who has not by the age of puberty "been irreparably scarred by the conditions of his life.

"The wonder is not that so many are ruined, "but that so many survive."

(fire crackling) Mamie: I was seven years old, we had to leave Mississippi because they was going to lynch my father.

(slow somber music) My dad went to work that night, he came home.

He said, "Rochelle," he said, "I have to leave now.

"So you get ready, and get the children ready, "and you leave in the morning."

They were going to lynch my father.

We were frightened, but I was too young to know what they was talking about.

My dad, no, he didn't take nothing.

So I don't know what happened, whether he got in trouble, you know, with some of the bosses, I don't know.

But as far as I know, we had to leave, and he had to leave.

And then there was a friend of his, John Hartfield, that was his name.

They accused him of molesting a White lady, and they were going to kill him then, but he got away.

So when my dad left, he came with my dad.

Tarabu: No one really knows why my grandfather, Edward Lang, came home from the lumberyard in fear of his life that night, or what, if anything, he was accused of, but the reality is, is it was 1915 in Mississippi, and any look the wrong way or perceived slight by a Black person towards a White person could cost you your life.

Mamie: My mother got all five of us ready, got on a train and went to East St. Louis, Illinois.

We were running for our lives.

(soft somber music) Tarabu: The conductor was harassing my grandmother.

He refused to believe she was telling him the correct ages of her children and insisted that she pay more money for their fares.

Mamie: And my poor little mother, bless her little heart.

She had it on the train, battered her all the way, until she told the conductor, "Well, I guess you know, you're the father."

And when she told him that, he left my mother alone.

They could have thrown us all off the train then.

Murdered us and nobody would've, they wouldn't have cared.

Let's talk about something else.

Bryan Stevenson: What most people in this country fail to appreciate is that the demographic geography of America was shaped by lynching and racial terrorism.

At the turn of the 20th century, there were millions, most African-Americans lived in the American South.

but by World War II, millions had fled and the Black people who fled Mississippi and Alabama and Georgia and Louisiana, and went to New York and Cleveland and Detroit and Rochester and Los Angeles and Oakland.

The Black people who went to those communities didn't go to those communities as immigrants looking for new economic opportunities.

They came to these communities as refugees and exiles from terrorism in the American South.

Tarabu: In September, it'll be 100 years.

Mamie: That's right.

Tarabu: Since you left Mississippi.

So I've asked you several times if you wanted to go back there.

Mamie: Who me?

Oh, indeed not.

Nobuko Miyamoto: I think Mamie's resistance to Mississippi is something like what my folks went through coming back from concentration camps.

They didn't wanna talk about it.

They buried their trauma.

We have this saying, (speaking in Japanese), Shikata ga nai don't cry over spilled milk, just go on with your life.

But meanwhile, my father didn't believe in the system anymore.

He never voted for the rest of his life.

Tarabu: But in some ways when these issues are referenced, you can see how it's still sort of buried in her, you know, cellular memory, and it's deep.

That's why to me it's, it's so compelling when I think about being gone from Mississippi over a hundred years, yet still the effects of that moment linger.

(slow somber music) Narrator: "This was the culture from which I sprang.

"This was the terror from which I fled."

(slow somber music) Mamie: We got to East St. Louis and was there for a couple of years, then the race riots started.

Cameron McWhirter: People wanted to get away from the violence that was taking place as a result of Jim Crow, and going north was a way to build a new life.

We had African American workers going up to get jobs and White workers heavily resented it, and then that led to rioting, and that's what happened in East St. Louis.

(slow somber music) Mamie: The race riot was so bad they had to bring in the National Guard.

We couldn't go out.

My dad was working, he wanted to come home.

They wouldn't let him come home.

And my uncle, he was with us and he was saying, "Don't worry, you'll be okay."

And the prayer he sent up that night, oh my uncle prayed and prayed and prayed.

Well, my dad couldn't come home in a week.

It was a horrible sight.

Fighting, shooting, killing our people.

That I remember clearly.

This particular man was walking down the street, they told him, "Halt," told him one time, told him twice.

And the third time, they stuck a bullet through him.

He was deaf.

That was a horrible tragedy.

We had moved in a neighborhood where there were only two Blacks.

If they came and Blacks lived there, they would burn your house down.

So it was two neighbors lived together, Mrs. Sanders, I won't forget it, and my father.

And so they came that night with the torches.

The landlord, he liked my dad so much.

And they told them when they got to our house, they said White lived there, and that was the only thing that saved us.

And that went on for, oh my, it was so long.

Cameron McWhirter: Thousands of people streamed over into St. Louis to get away from being killed.

Certainly the African American community felt that they had been abandoned by local government, state government, and the federal government after East St. Louis.

If you look at the history of America, every decade there was a race riot, and the vast majority of those riots were White mobs attacking individuals or Black communities.

(slow solemn music) Tarabu: What happened between your mother and your father?

Why, why did they eventually separate?

Mamie: I couldn't tell you, but my mother wasn't a pastor's wife.

Tarabu: She wasn't a pastor's wife?

Mamie: Mm-mm.

(both laughing) Pretty and cute, cute as a button.

So that's all I got to say.

(laughing) (children chattering) I was very shy when I was coming up.

Never talked much, never around a lot of people.

I was to myself most of the time.

I really liked to read.

I'd be up 3 or 4 o'clock in the morning reading.

And then you had no electricity, we just had lamps.

Book after book, and I'd usually read the Bible a lot 'cause I'd write my Daddy's sermons, you know.

When he'd come into work at 12, I'd stay up, and my dad and I would be up sometimes, 3 o'clock in the morning writing his sermon to preach the next day, and that's when he taught me so much about the Bible.

What life was all about.

and my mother would get up in the morning, she'd say, "Gold baby.

"Do you know what time it is?

You go to bed."

And I loved to write, and I loved to read.

If my dad and my mother had've known what an education meant then, I'd probably have been in the White House.

(all laughing) Tarabu: So did you, did you ever have any anger towards White people?

Mamie: Never.

Oh, I was frightened by it, but I never had that, you know what I never had that issue about color.

It was just bad people and good people, you know?

The way you come in the world, that's the way the Master wants you here.

Why am I gonna get mad with James with his color?

What good would that do me?

With all I went through with, mm-mm.

You're a person and I'm a person.

(slow solemn music) Narrator: "The lazy laughing South, "with blood on its mouth.

"Passionate, cruel, honey-lipped, syphilitic, "and I who am Black, would love her.

"But she spits in my face, so now I seek the North.

"The cold-faced North, where she, they say, "is a kinder mistress."

Tarabu: When did you leave East St. Louis?

Do you, do you remember?

Mamie: I know it was after the race riots.

My dad was working for Aluminum Ore Company then.

After the riot then they opened up the plant in Alliance, Ohio.

My dad decided he would go where he could get a better job, you know, and more money with all the children he had.

This was a all-White section, no Blacks supposed to be there.

The school was right where we were, walked right to the school, right on the corner.

Tarabu: An all Black school?

Mamie: No, it was a White school.

Tarabu: It was a White school?

Mamie: Yeah.

Tarabu: Well that's interesting.

You went to school in Alliance, Ohio, in an integrated school, and you didn't have any problems whatsoever?

Mamie: No problems.

There were other Blacks going to school there, you know.

But they didn't want us on that street.

They didn't want no Blacks on that street.

(crowd shouting) The Ku Klux Klan didn't want us there.

They were going to burn our house down.

So the German living next door loved my Dad.

He said, "Reverend Lang, don't you worry, "because we're right here next door to you, "with the Lugers, with the guns.

"And if anything happens, we will be with you."

We're just shaking, frightened to death.

They came, each one of them had torches.

They burnt the cross, but they didn't get the house.

The Lord didn't let it happen.

But that was a horrible experience, to see those men with those big tall hats on, with those torches in front of your house, and we children are just shaking.

And my dad kept saying, "Don't worry, "everything's gonna be okay," and so it was.

(slow solemn music) (slow solemn music) Narrator: "And so the root becomes a trunk, "and then a tree, and seeds of trees "and springtime sap, and summer shade, and autumn leaves "and shape of poems and dreams, and more than tree."

(march drum music) Cameron McWhirter: After World War I we were the economic powerhouse of the world.

A lot of really good things were happening for African Americans at that time.

They're expanding their economic power and their, and even their political power.

African American soldiers had fought in World War I.

There were certainly a lot of people at that time who were espousing this idea that White civilization was under threat.

Bryan Stevenson: This new wave of anti-Black violence was spreading throughout the American South.

And at a moment when we should have been reflecting soberly about what a democratic society requires, what being committed to the rule of law requires, we were doing the opposite when it came to African Americans.

Cameron McWhirter: So the Red Summer was named by James Weldon Johnson, the famous writer, and NAACP activist who called it the Red Summer because it was so bloody.

If, if people had learned from East St. Louis, the Red Summer may not have ever happened, but they didn't.

This issue of race just runs like lightning through American history, and the Red Summer is the worst explosion of that anti-Black violence.

Echoes of that are echoing today.

Beginning around April, 1919, and running through till October, November, thousands of people lost their homes, hundreds of people were killed, governments were shut down.

It was a real disastrous, chaotic period.

Tarabu: But for you personally, what effect do you think it had on you, having to go through all those experiences so young?

Mamie: Well, I guess it made me a little bit stronger, to know how to take things.

Whatever happened, it happened, but you'll never forget it.

(slow somber music) (slow somber music) ♪ Remember if you can ♪ ♪ When cotton was picked by hand ♪ ♪ Down in Dixie under Southern skies ♪ ♪ Working from sun to sun ♪ ♪ I can hear the Delta calling ♪ ♪ From the light of a distant star ♪ ♪ I can see the future I can feel my past ♪ ♪ When Henry play his steel guitar ♪ ♪ Remember, remember, remember ♪ Tarabu: I received an email from a friend in the beginning of 2015, and there was a link to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative, titled Lynching in America.

And as I was thumbing through the report, there before my eyes was a front page article from a June 26th, 1919 edition of the Jackson Daily News, Mississippi's largest newspaper at the time, and this was during the height of the Red Summer.

And the title of the article read, "John Hartfield will be lynched by Ellisville mob at 5 o'clock this afternoon."

and I just stood in my tracks.

I had heard John Hartfield's name hundreds of times as a man who fled with Mamie's father in 1915, fearing they both would be lynched.

But this was the first time I'd ever seen anything documented.

My mother was here in California at the time, and I said, "Is this the man you've been talking about "all of these years?"

And literally, before I could finish the sentence out of my mouth, she pointed to the laptop and said, "That's him."

I could just feel the hair stand up on my back, it was that riveting to be met with this digital confirmation.

How many people were actually lynched during the Red Summer?

Cameron McWhirter: Well, we're never gonna know the full number, and part of that is because certain areas never wanted to fully investigate it.

We know some of them.

Ellisville was the worst, being the most flagrantly public.

Tarabu: As long as I can remember, the backstory about John Hartfield as my mother recalls it, has always been that he had a consensual romantic relationship with Ruth Meeks, the White woman he allegedly assaulted.

He had already evaded capture once several years earlier, but decided to return in 1919, and met a tragic end.

Mamie: And my father tried, told him not to go back.

But he didn't listen.

Tarabu: John Hartfield was pursued by a posse and a pack of bloodhounds for over a week, through the backwoods of Mississippi.

When he was finally captured, he was clubbed and mortally shot, but kept alive in a doctor's office overnight so he could be lynched.

Cameron McWhirter: It's announced to the public and to the press that they're gonna lynch this person the next day.

The NAACP tries to get involved and appeals to the governor, and he basically says, "Well, what can I do "when someone commits rape?"

The fact being that he was never charged, he was never went to court, he was never, we don't know what happened.

Tarabu: One reporter by the name of Hilton Butler who witnessed the lynching, gave this account.

Narrator: I saw and reported the lynching of John Hartfield in Ellisville, Mississippi, but there were at least 10,000 people in the pasture.

I had to drop from a tree behind Hartfield to escape bullets fired at his swinging body.

(gunshots blasting) Every time a bullet hit it an arm, out it flopped like a semaphore.

My newspaper account of it said not less than 2000 bullets were fired into his body.

One of them finally clipped the rope.

John's body fell to the ground.

A fire was built around it, and John was cremated.

(fire roaring) That night a grinning man in Laurel exhibited a quart jar with alcohol, in which a finger cut jaggedly from the Negro's hand bobbed up and down.

"I got a finger, by God, and I got "some photographs of him hanging, too.

"These photos are 20 cents each, "but ain't, nobody can buy this finger.

"I cut it off from him myself.

"That n-- was tougher than the withers of a bull.

"And he screamed like a woman when I done it."

He sold out of the photos quickly.

I bought some myself, as many as I could, and tore them up when I got out of sight.

Mamie: It was a sad feeling.

It was deep.

Coulda happened to my father.

He could not never got home to let my mother know what was happening, you know?

Many families had to vacate from the South, and many was lynched there.

Cameron McWhirter: The Red Summer was a horrific spate of violence, but something really amazing happened that year with the NAACP, and I would argue it's the beginning of a long Civil Rights Movement.

Blacks as a collective body started to fight back.

(slow solemn music) (slow solemn music) Narrator: "I was leaving the South "to fling myself into the unknown.

"I was taking a part of the South "to transplant in alien soil, "to see if you could grow differently.

"If it could drink of new and cool rains, "bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth "of other suns, and perhaps to bloom."

Mamie: My dad had this big house and they wanted anybody.

They had room for roomers, to take them in, and that's where I met my husband at.

My husband and his friend, they was working on the railroad, and they were coming to work in the plant.

So my dad took them in and my dad thought a lot of him.

He loved your father.

Tarabu: So how did your husband come on to you?

Mamie: I, I couldn't tell you.

(laughing) Tarabu: How, how did he, he romance you?

Mamie: Well, I guess he, (laughing), you know how romance is, I don't have to tell you that.

Your dad was a good-looking man.

Sharp, you know, the clothes.

(laughing) So when he did ask my dad for, to marry me, he said, my father said, "As long as you treat Gold baby right."

My Daddy married us, and I'm only 15.

And when they asked us for the ring, no ring.

It was funny.

(laughing) Tarabu: So your husband didn't have a ring for you?

-: No we didn't have no, what kind of ring?

I didn't know nothing about no ring.

And you see those shoes your Daddy got on, those shoes were sixty dollars, then he didn't wear nothing cheap.

Tarabu: That's pretty expensive shoes back then.

Mamie: Yes indeed, and he got nothing, he had no cheap shoes.

And he would get angry with me, because I'd buy cheap shoes.

(laughing) Tarabu: Did you know that you loved him?

Mamie: Oh yes I did, and he loved me.

We went to Buffalo that May, because my husband's parents were, you know his family was there.

So he left and got a job, at Pratt and Letchworth, then he sent for me.

I hated Buffalo, I cried for many days, wanting to go back home.

Sit on the Corner of Clinton and Jefferson when the kids come from school, crying, wanted to go back to school.

If all that had happened, I would have been an English teacher like I wanted to be.

That's what I always wanted to be, an English teacher.

Didn't know how to cook, (laughing) my husband had to learn how to cook.

Tarabu: My mother had nine children and one miscarriage, which she always counts.

I'm the last child, the baby boy.

She had her first child at age 16, and by the time she was 26, she had already had six children, but lost three of them to early childhood illnesses.

Your father prayed for you, he said, "I pray for God to send me a son."

So I put my hands on my hip, I remember, "Are you crazy?

"I've had eight children and I'm not having anymore."

And 12 years later, you, the God-sent boy.

Nobuko: You wanna know what the numbers are today?

Mamie: Yeah.

Nobuko: How long you been playing the numbers?

Mamie: Ever since the Depression.

Nobuko: So everybody was playing?

Mamie: Oh yeah, that's how we lived.

Nobuko: Through the numbers?

Mamie: Yeah.

Nobuko: Why?

Mamie: Because you could take a penny and get $5.

You could get as much food for $5 as you do now for $25.

Nobuko: Maybe more.

Mamie: It's a lot.

Nobuko: 555.

Mamie: Mm, mm Nobuko: And 839.

Mamie: Nothing I had.

(soft somber music) Mamie: The Depression was coming up and it was horrible, my husband wanted to work.

The plant had closed down.

just he'd be work, one or two days, but that wasn't enough to feed a family.

But we had it so bad my mother came to live with me.

My stepfather, my cousin, my husband's cousin, my three children and I, eight people in one house and guess how much they gave us?

Six dollars and 75 cents a week.

Then my stepfather started working on the boat and my dad and my mother would go fishing and they would get this big tub of fish and we'd feed the neighborhood, and they were so happy.

It was horrible, but we made it.

Tarabu: My mother had a favorite line that she often used when the topic of Mississippi came up, which was, "I don't even want to see it on a map."

She said after her father fled Mississippi fearing that he would be lynched, he never spoke about it again for the rest of his life.

Why don't you wanna go back?

Mamie: I just, I don't know, I just don't wanna go back.

Tarabu: You always tell me you, you would never go back there, but then you said right now that you're, you're not afraid of anything.

Mamie: Well, I'm not afraid to go back but I don't, I don't want no parts of Mississippi.

Mississippi is not on my mind.

Interviewer: Can you understand why to Tarabu wants to go?

Mamie: Yes I, I understand exactly what he's talking about.

Nobuko: Mom is not exactly your normal 111 year old.

She's interested in the world today, still.

We would be sitting at the breakfast table and I'd be reading the newspaper and she's asking me, "Well, what's going on?"

At that time, there were a lot of killings of Black men by police, and demonstrations of Black Lives Matter, and I'd talk to her about it.

Then the killings in Charleston, and she looked at me and she said, "The same thing that happened to my family "in Mississippi is going on today."

That's when I can see the wheels in her head turning.

Tarabu: I tried every angle I could think of to get her to reconsider going back to Mississippi.

Her response went from, "What part of no "don't you understand," to, "I don't know, and don't ask me again," to, "Let me pray about it."

I knew it would be a challenging journey for her physically and emotional, so I didn't push it, but I knew I had to go back, but I also knew it would only be meaningful if she went with me.

She was 107 at the time with a long legacy of almost 160 grandchildren and nothing to prove.

Still, I think there was one stone that was left unturned.

This was our story and we had to tell it, and she felt the momentum building around it, and eventually she claimed it.

Bryan Stevenson: Many people of color are forced to not talk about their burden.

The idea that your mom would come back to Mississippi and go to this place she had not returned to, that had been such a place of anguish and stress at the moment of her exodus, and make it sacred with her heart and with her prayers and with her family, it makes me believe that we can change what this legacy represents.

Mamie: When you said you was going down there, I said to myself, now I can't let you go down there without me.

And you said, "Would you be afraid to go back?"

No, I'm not afraid as long as God's with me.

And I never thought I'd think that way again.

But when God tells me to do something, I have to do it.

And now that I could go back and wouldn't be chased out anymore, I can make it.

(soft thoughtful music) (soft thoughtful music) (soft thoughtful music) (soft thoughtful music) Paul Mones: Tarabu said to me I'm going to Mississippi, and we're leaving, I thought, "Wow, this is just a great story."

So I called the Equal Justice Initiative, and I called Tarabu and said, "Oh, they're gonna, "they're gonna call you."

Kiara Boone: It was so nice meeting you, thank you.

Bryan Stevenson: It was a real thrill to meet her and, and to see her in action.

She can articulate every aspect of what it means to be a human being who has survived terrorism and segregation and bigotry and bias.

And yet have this hope, this joy, this love, this life.

Paul Mones: And then I thought oh, they're going down there, and because of the kind of work I do, I have different affiliations with different reporters around the United States.

And I called this reporter from the New York Times.

and I said to him, "This is a really good story," and he couldn't believe the story when I first started talking to him, he said, "No the woman is, you're talking about a hundred years ago."

Dan Barry: I think that the experiences that you went through might've broken other people but you seem very resilient and strong.

You find strength in your family and your faith, right?

Mamie: Absolutely.

I've always had that faith, from a little girl up.

Dan Barry: You're glad you came back?

Mamie: I'm glad.

Tarabu: She was here in Ellisville for the first time since 1915, and we weren't sure what to expect.

We drove past the Jones County Courthouse that was built in 1908, the same year she was born.

The marble Confederate soldier was standing in defiance out front, erected when she was four, and two identical drinking fountains with plaques covering up the inscriptions, White and Colored.

The main square looked like photos we had seen taken 100 years ago, but despite the passage of time, we knew there was a dark secret buried underneath these slabs of concrete that had never been acknowledged or reconciled.

Our very small family pilgrimage transformed once we connected with the Truth and Reconciliation Movement spearheaded by the Equal Justice Initiative.

Now her story became part of the narrative confronting history and talking about racial terrorism, and rewriting that legacy, because telling our stories is what keeps us alive.

So when we were contacted by EJI, one of the things that came apparent to us was that we had to do a search for the site where John Hartfield lost his life.

Jennifer Taylor: So you can see there's like all these people.

Walter Clark: Oh gosh.

Jennifer Taylor: Yeah.

Jennifer Taylor: But it's hard to tell quite where they are, but there aren't like a lot of buildings around.

I think the train tracks might've been over here.

There's this here that I hadn't seen before.

Walter Clark: That's the hotel.

Jennifer Taylor: Right, that's the hotel.

Tarabu: The Alice Hotel?

Jennifer Taylor: Yeah.

Walter Clark: The Alice Hotel.

Tarabu: Wow.

Jennifer Taylor: And that's people kinda standing on it but, and it seems like that might be the place that they pulled him from, because in the newspaper articles it says that they had taken him to a doctor's office, and asked the doctor to kind of help him survive until they could prepare for the lynching.

Tarabu: So in their research, they interpreted it to be on Pine near the railroad tracks and she said there's a concrete platform there where they used to hoist victims up for lynching.

Cameraman: Should we go look at it?

Tarabu: We should.

(soft somber music) (soft somber music) Klan Member: I think a n-- has rights in this country.

He should have equal rights, but separate rights.

It worked for 100 years in the South, and I think it will work now.

Klan Member 2: I read in my history books the n-- race was an inferior race.

They always have been, they always will be.

(people screaming) (people screaming) Nobuko: So we're gonna get out of the car here.

This is the place that it happened.

Mamie: Oh no.

Nobuko: Yes.

Mamie: Never saw him in my life.

Nobuko: Yeah.

Tarabu: So we just wanted to, just memorialize this moment for all of us, and not just come and be here as a, a viewer and a spectator, because this is part of our living history, so I wanna pour a little libation here for John Hartfield.

(water splashing) And this is for all those others who suffered a similar fate, (water splashing) and this is to water the spirit of all those who were still standing tall and strong against this violence.

(water splashing) Ase.

(soft solemn music) (soft solemn music) Bryan Stevenson: We've had this project where we invite people to go to lynching sites and to collect soil and put it in jars to honor these victims of lynching.

And that's what's been really, really powerful in having Mrs. Kirkland come back to Mississippi to kind of engage in that remembrance.

For us it has been really, really meaningful, 'cause I think soil is a powerful medium for telling this story.

The sweat of enslaved people is in the soil.

The blood of lynching victims is in the soil, but there's also life in the soil.

We can actually plant something that imagines a different future and it will grow.

(soft gentle music) Mamie: I thought I would never go back to Mississippi.

But see how things can change.

I had no fear, treated royally, didn't get nervous or nothing.

And I'm so glad I went back to see where I was born.

So it was meant for me to go back.

(soft profound music) Tarabu: Were are you surprised how many people responded to your story?

Mamie: I was, I didn't know nothing like that was happening.

And still it didn't dawn on me, you know, exactly what it was meaning that day, it didn't, 'cause I had no idea.

But everybody kept telling me, they'd say, "Oh, what a beautiful write-up that was."

I kept thinking to myself, "What have I done "To make all this conversation with people?"

And so one of the assistant minsters said, "well you know what, you've done something to help all these young people, that never knew what happened."

That things was happening, put under the ground, which is true.

'Cause a lot of people don't know nothing about this.

The young people to know what was happening, which they don't teach them that in school, you know?

And I know what happened, I'll never forget.

(soft poignant music) (soft poignant music) (soft poignant music) Racism is still deeply rooted-- (Mamie gasping) Exhibit Orator: The strength of this country.

But today as the world seems almost to unravel around us, there is much, there is much to defend from.

Mamie: Oh look at that, 1917.

Tarabu: You were there.

Mamie: I was right there.

This is something to see.

Bryan Stevenson: We do a lot of things great in America.

We do success great, we do pride great, we do victory great, but we don't do shame great.

We don't own up to the things about which we should be shameful, and I think that leaves us vulnerable to replicating those things.

I think if we had made the right response to lynching in the 1930s and '40s, it wouldn't have taken another 50 years to accomplish the Civil Rights Act.

If we'd made the right response to that violence, we could've created a culture that began to appreciate and respect the victimization of all people, not just people who are White and affluent.

-: [Museum Display Narrator] Pack up everything you can fit into two or three little."

Tarabu: So these are the markers up here on the top of the hill.

Mamie: Oh, there.

Tarabu: Markers with the names of all of the lynching victims.

(soft solemn music) (soft solemn music) Mamie: With all those hanging names of the people that was lynched.

You know, it took us all day to go through that museum.

Tarabu: It had a big impression on you.

Mamie: Oh yes, but then when I got to 1917 with the race riot and everything, that got me.

The children, families lynched, and I was right in it.

I was right in it, I couldn't see it that night.

But I'm getting back the normal now, you know.

And I'm so glad that God abled me to live long enough to see what happened during the years of my life, and that's a blessing.

Tarabu: That's a blessing.

Walk over.

Let me see that beautiful hat you got on, look at that.

All ready for tonight?

-: Uh-huh.

(soft expectant music) Bryan Stevenson: Ms. Kirkland, we wanna say to you how much you've inspired us.

You have done something so courageous, and what you represent are our mothers, who had to endure segregation, and all of the humiliation that people tried to expose you to, but you endured it, and you loved us, you nurtured us, and you taught us to keep fighting.

(crowd cheering) Mamie: You know I'm so grateful to God that he wanted me to live to be able to tell the story.

I left Mississippi 100 years ago, because they were going to lynch my father.

I left there a frightened little girl at seven years old, but you know what?

I'm not frightened any more.

(crowd cheering) (mid-tempo inspiring music) (soft gentle music) Narrator: "I must confess that I still breathe, "though you are not yet free.

"What could justify my crying start?

"Forgive my coward's heart, "but blame me not, the sheepish me, "for I have just awakened from a deep, deep sleep.

"Black mother, I curse your drudging years, "the rapes and heartbreaks, sweat and tears.

"But I swear on siege night, dark and gloom, "a rose I'll wear to honor you.

"And when I fall, the rose in hand, "you'll be free, and I a man."

(mid-tempo majestic music) (mid-tempo majestic music) ♪ It's a cloudy day, no sunshine ♪ ♪ It's cold, gloomy, and gray ♪ ♪ Oh, I have felt much better ♪ ♪ And I've had my ups and downs along the way ♪ ♪ But when I look back, I just laugh ♪ ♪ And all my troubles just melt into the sea ♪ ♪ My vision is clear in the aftermath ♪ ♪ And the future looks marvelous to me ♪♪ announcer: Funding for "100 Years From Mississippi" was provided by: The Angell Foundation, Josephine Ramirez & The James Irvine Foundation Staff Matching Gifts Program, Julie Mount Donor Advised Fund, Paul & Nicole Mones, Mamie Kirkland, Barry Shabaka Henley & Paulina Sahagun, Patty Hirota-Cohen & Lewis Cohen, Ellie Kanner, and Kat Taylor.

Support for PBS provided by:

100 Years From Mississippi is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television