Interview with Gary Glassman

Clip | 45m 19sVideo has Closed Captions

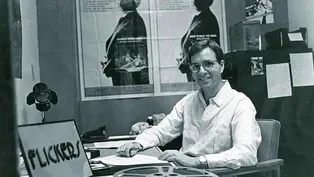

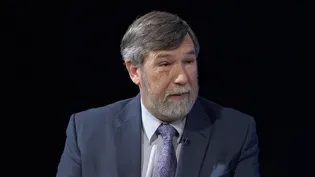

Steven Feinberg interviews Providence Pictures' Gary Glassman.

Steven Feinberg, executive director of the Rhode Island Film and Television Office, interviews Gary Glassman. Glassman is a documentary filmmaker based in Rhode Island and the president of Providence Pictures.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

doubleFEATURE is a local public television program presented by Rhode Island PBS

Interview with Gary Glassman

Clip | 45m 19sVideo has Closed Captions

Steven Feinberg, executive director of the Rhode Island Film and Television Office, interviews Gary Glassman. Glassman is a documentary filmmaker based in Rhode Island and the president of Providence Pictures.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch doubleFEATURE

doubleFEATURE is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(upbeat music) - Hi, I'm Steven Feinberg, executive director of the Rhode Island Film and Television Office.

Our guest tonight is a highly acclaimed documentary filmmaker whose works have been showcased on Rhode Island PBS, BBC, Discovery, and so much more.

I wanna welcome the founder and director of Providence Pictures, Gary Glassman.

Welcome to "doubleFEATURE".

- Thank you Steven.

Nice to be here.

- So Gary, you've been making documentaries for how long?

- Oh, my first documentary I think was in 1985.

- Wow.

And now was that "Prisoners?"

- That was "Prisoners," yes.

- Can you tell us about "Prisoners?"

- Yeah.

Well first of all, I was always fascinated by television.

And the big inNOVAtion in my lifetime was VHS.

- Yes.

- I mean, VHS represented the democratization of production and distribution.

And so I started thinking about that in relationship to storytelling, the ability of normal everyday people being able to tell their own stories.

And I thought, who would we like to hear from that we don't normally hear from telling their own stories.

And I thought prisoners.

And at the time I got a grant from the California Arts Council and the Department of Corrections to go in and start doing workshops for prisoners, actually making films with them, short films on VHS.

- Yeah.

- And also at that time, I met an incredible artist, Jonathan Borofsky.

And so much of his work was about learning to be free.

And we got into a conversation about what does that mean?

And he was exploring freedom with thought leaders, you know, from the spiritual world, from the political world.

And I suggested, well, maybe we could learn something about being free from people who are the least free.

And he really liked that idea.

And he said, if you can make it happen, let's go interview prisoners.

And that's how it came about.

- So this is in California?

- Yeah.

- Which prisons did you go to?

- We did a number of them throughout the state.

San Quentin.

- Yep.

- Was the most famous.

But we also, California Institution for Women, California Rehabilitation Center.

California Institution for Men, and a few others.

- Did you ever go to Pelican Bay?

- I have not been to Pelican Bay.

- Oh, okay.

That's where the prisoners who can't navigate the regular prison system, it's a supermax, if you will.

- Yeah.

- So how long did that process take?

- The film "Prisoners," we worked on it for about probably a year, and it premiered at the American Film Institute's National Video Festival, and was bought by the Museum of Modern Art and the Pompidou Center in Paris.

- And that was your first documentary?

- Yeah.

- Your first documentary is at the Museum of Modern Art.

- Yeah.

I got lucky.

(laughs) - That is, well, that's gonna be inspiring.

Alright, so let's backtrack.

You were born where?

- In the Bronx.

- Okay.

- Bronx, New York.

- Okay.

- Grew up in Buffalo.

So I'm a Buffalo Bills fan.

- Yes, yes.

Okay.

And I was told, and tell me if this is true, that you joined a circus.

- I was going to a college in Vermont called Goddard College, and I had plans to go to Chile and study the education system there under the new socialist government.

And as I was on my way there, there was a coup d'etat and I decided I should turn around and go back to Goddard in Vermont.

And I had no plans.

I didn't know what I was going to do, what courses I was gonna take.

And this clown troupe showed up for orientation day, and I fell in love with this clown troupe.

It was all clown circus.

They reached me and I'm sure the rest of the audience at a level that is just primal, you know?

And their show was about, you know, themes of love, and jealousy, and greed, and revenge.

And I thought I'd like to do that.

And the theater company, the Two Penny Circus, was invited to become the artist in residence that semester.

And so I took a class with them, clowns, and I just, I fell in love with it.

And one thing led to another.

And after I graduated, they invited me to join.

- And where would you guys perform?

- We performed around the world.

We performed throughout the United States, but also Europe.

- Wow.

And were they privately funded or how would?

- Yeah, it was us.

We made it happen.

- And how long did you do that for?

- About three years.

- What an experience.

- Oh, it was great.

- Did at some point, what caused you to say, okay, now I'm coming home, I'm going to?

- I guess I wanted to explore more.

- Yep.

- I mean, interestingly, you know, in retrospect we were kind of a proto Cirque de Soleil.

And I, you know, had I stuck with it, I don't know, you know, what my life would've been, but I wanted to do more and I wanted to, you know, like I said, around that time I discovered VHS.

- [Steven] Right.

- And so I started wanting to make films.

- And were you looking just to, because obviously you're almost living a gypsy life, right?

In that as a circus performer?

- Well, we were based in Vermont.

- Oh, okay.

- And then we would travel from there.

- Oh, okay.

- So, you know, we'd be on the road for weeks at a time.

- So what brought you to Los Angeles, 'cause that's where you went next?

- Yeah, so I was in New York after Vermont.

I moved to New York, and I was part of the whole performance art scene down there, doing street theater and playing in clubs, like the Nuyorican Poets Cafe.

And I was doing a one man show based on Henry Miller's work, and I decided I'd like to go meet Henry Miller.

So I went out to Los Angeles and tried to meet him.

And not successfully, but I stayed in Los Angeles.

I lived in Venice.

I was a block off the beach.

- Yeah.

- I mean, it was like, you know, it was Venice, California was great.

- You're right.

I know those stomping grounds.

(both laughing) And then what?

You met your wife and that brought you to Rhode Island?

- Yeah, so I was in Los Angeles for many years.

In total, almost 20.

- We were in Los Angeles at the same time.

- Yeah.

When we just discovered, we were at actually at UCLA at the same time.

- At the same exact time.

- Yeah, yeah.

- So, and I was there for 22 years.

And you were there for 20?

- Almost 30 years.

- Oh, okay.

- Yeah.

Oh, I'm sorry.

No, I was there for 20 years.

- Right.

Yeah, yeah.

- And so then tell me how you?

- So I met my wife.

She was a visiting scholar at the Getty Center, and we met at a reception there.

We fell in love, and she had a position at the (indistinct) the following year.

And so I kind of hustled and got myself a commission to write a screenplay, and I moved to Paris with her.

- Wow.

- So we lived in Paris for a year, and then she got a job offer from a place called Providence College.

- (laughs) A place called Providence College.

And hence, you came back to, you came to Rhode Island, and that's when you formed Providence Pictures.

- Yes.

- The Prestigious Providence Pictures.

- Yes.

- What were your plans for that when you were founding Providence Pictures?

- Well, again, I was just very lucky.

I was a very good editor, and I met a young producer who had just gotten a few shows for the Discovery Channel, and he hired me as an editor, and we teamed up and we made about 12 programs for Discovery together.

- Yep.

- And then when my wife was pregnant with our daughter, I decided I didn't want to commute to Boston that much anymore, so I opened up an office in Providence, Providence Pictures.

- Right, right.

And what was the goal?

Did you have a goal in mind when you started this, or you just winging it?

- Well, again, very fortunate that my partner and I were very successful with Discovery Channel and Discovery said, yeah, you wanna go on your own, we'll give you more shows.

So I had a nice portfolio of programs that I could make and that just sort of launched Providence Pictures.

- Now, what was the first production that came out of Providence Pictures?

Was that "Bibles Buried Secrets," or was this something before that?

- There were a series for Discovery Channel for a series called "Discover Magazine."

And then I did a number of specials for Discovery Channel and History Channel.

And then I started getting NOVAs on PBS, and "Bibles Buried Secrets" was one of those programs for NOVA.

- [Steven] That was, I think we met right around that time.

Was that like 2005, maybe 2006?

- Yeah, maybe 2008.

- Okay.

- Some somewhere in that area.

Yeah.

- Yeah.

And then you were also able to access the Motion Picture Tax incentive program that we have here in Rhode Island, which is really, it's to encourage filmmakers like yourself, to support as well as the productions, the Hollywood productions, which support our local crew.

And has that proved to be a helpful tool for you?

- Absolutely.

You know, the tax credit here has kept Providence Pictures going through a lean times and no, it's been incredible.

And now, you know, I'm proud to say that my daughter is a filmmaker and she's been able to tap into the tax credit as well.

- Excellent.

And so you've inspired your daughter to follow in her pop's footsteps?

- I could not discourage her.

- (laughs) Now do you have full-time people on board Providence Pictures, or is it primarily yourself?

And how many people would work in one of your, like for example, the "Bible's Buried Secrets," how many people work on that?

- I don't remember how many were at that time, but we just came off of two seasons of "Native America" for PBS.

- Yep.

- And we had at least a dozen full-time people.

- Yep.

Now, when you're working on a show like "Bibles Buried Secrets," is there location filming that takes place on that, or?

- Oh yeah.

I mean, that's the thing about documentaries.

You know, it's rare that you get to stay home and make a documentary from home.

- Yep.

- We travel everywhere.

Our "Building Wonders" series where we looked at iconic buildings around the world from ancient times and looked at them as almost like snapshots of that society at that time.

So the Parthenon, cathedrals, the Sphinx, Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, and I'm sure I'm forgetting some others, but we go there and, you know, we work with local people there, examining those buildings.

So for one of the conceits of that series was, we would look at one aspect of that building.

So in the Colosseum it was lift and trap door system.

They would do these incredible, you know, gladiatorial events and- - With animals, live animals.

- Elephants would appear from underneath the stage.

And we thought, - Tigers and.

- Tigers, lions.

Actually, they killed so many beasts animals in the Colosseum that a few actually went extinct at that time.

- Wow.

- It's horrendous on, you know, so many levels.

- Right.

- But we wanted to look at, you know, how did they do it?

So we worked with an archeologist who thought he knew how they created this lift and trap door system in the Colosseum.

And so we worked with him and some engineers and actually built a lift and trap door system, installed it in the Colosseum and released a wolf into the arena.

It was the first time a wild animal was released into the Colosseum for, I think 1500 years.

- Wow.

You didn't lose any production assistance, did you?

- No, no.

- (laughs) You didn't sacrifice anybody.

When you're working with a company, whether it's NOVA or the History Channel, or BBC, are you pitching to them, or are they coming to you about particularly, or do they say, hey Gary, we have this budget, this is what we want to do.

How does, tell me how the process works.

- Well, I've been fortunate in that I've basically been pitching, I mean, it's got its pros and cons.

I get to pitch what I'm interested in doing and, you know, try to sell the idea.

- Yep.

- To these different broadcasters.

- Do you, let's say, have a many piles of ideas and that you've done some research on, and then you say, okay, this one's ready to go, this is the one I want to pitch?

Or is it just singular ideas?

- Well, there've been many, many over the years.

- Yeah.

- And after so many years, I tend to sort of like return to some that I think maybe this one will work now.

So "Native America," I started pitching that in like 1999, and it wasn't until 2015 that we got commissioned from PBS.

- Now.

Okay we're jumping ahead to "Native America."

So that's your most recent multi-part series, right?

How many episodes?

- There were two seasons, four episodes per season.

- Okay.

And why don't you tell the audience a little bit about a, well, like what your pitch was about "Native America" and then what it became as you started to get deeper and into it.

- Well, I was doing a film for NOVA on Copan, this Maya city in the Honduran jungle.

And I mean, here I was in the jungles of Honduras in this city with incredible pyramid temples and sculptures of kings from over 400 year period, and the art and the architecture, its own written language.

And it was built somewhere between 400 and 800.

And I just thought, well, how did this happen?

And what else was going on at that time.

I knew it wasn't aliens.

- [Steven] Right, right, right.

- So I was wondering like, what was going on throughout the whole Americas at that time?

And that sort of was the spark for the inquiry into "Native America."

And the first series was really about the world created by America's first peoples.

And it was a world that most people didn't even know existed.

Over a hundred million people connected by trade and social networks that spanned two continents, cities with over a hundred thousand people in them.

It was rivaling bigger than London at that time.

Their own forms of government, democratic governments.

60% of the food in the world today was actually engineered here in, grown and engineered here in the Americas.

And so that's really what the first series was about.

But I think the inNOVAtion in terms of television from that series was that, we had native people telling their own stories, speaking about their own heritage, and history, and traditions.

And when we had the opportunity to pitch a second season, I thought it would be really good to take that even further, bring it to modern days, and look at contemporary Indian country and have native filmmakers producing and directing each of the hours.

- Which I thought was very, you had a premier.

And I thought that was terrific.

The idea that you had let them not only tell, well that the people in front of the camera were telling the story, but the people behind the camera were also telling the story, I thought really added a lot to it.

- Well, there's incredible talent in Indian country, incredibly talented native creatives, and this was a great vehicle for them.

And there was something that, you know, a shared history, shared experience that native people have after 500 years of genocidal policy and towards native people here in the Americas.

- And holding onto their culture, desperately holding onto their culture.

On your, in this show, you're exposing an audience to things that we don't see anymore.

I don't know, sometimes life goes by so fast and we're so used to the McDonald's type of lifestyle, so to speak, and brand names.

And I just remember for example, the woman who was I believe teaching her daughter how to do textile work.

- Yeah.

So that was part of the first episode, "New Worlds," it was called.

And we had Aaron Yazzie, who's a NASA space engineer who is Navajo, and he designed the drill bits on the Mars rover that's drilling into the surface looking for signs of life.

And the premise of that story was that, inherent in Navajo culture is a sense of, mathematics and engineering.

And they could be demonstrated through their weaving techniques.

And so Aaron visits with master weavers, a mother, and her daughter were, an an older woman.

She's like a grandmother and her daughter, and they talk about mathematics and engineering, you know, on Mars and in a Navajo rug.

- Right, right, right.

- And I mean, and while they're weaving.

And so, you know, this idea that, you know, natives don't live in teepees anymore.

I mean, here's a, they're rocket scientists and, you know, engineers, and doctors, and lawyers and politicians, so.

- And how they take that spiritual and cultural part of themselves and help us in our exploration of space.

- Yeah.

It's actually bringing forward their traditional knowledge and values, and infusing it into what's happening in modern life today.

- When you are, you know, starting a, you know, how much time are you spending doing research on, like, for example, the first season of "Native America," and you're in the jungle in your, our Indiana Jones from Providence.

And you're saying, you know, how did this all happen?

Are you then going to people who have written books and what's the process?

- Well, first it's the spark of curiosity.

- Right.

- But, and then reading and talking to people.

But then I think where I'm the smartest is, that I hire people who are smarter than me.

- Yep.

- And you know, I have just, I've had some really great researchers and writers, you know, working with me.

- How long does that process take typically to put together a first episode, let's say?

- Well, it, you know, again, it just depends.

But, you know, production, it's time and money and, you know, there's a certain balance you have to hit and- - Do you schedule like a feature film?

They would say, this is pre-production X amount of time, this is our calendar of production, this is our calendar or post, and this is when we need to deliver it.

- Yeah, we do that.

- Same thing.

- Yeah.

- Same structure.

- Yeah.

Yeah.

- What kind of budgets are you typically working with on a show?

- Well, you know, it's ranged from a couple hundred thousand to a million.

- Yep.

Okay.

I remember, I believe it was, I don't know if it was the "Secrets of the Parthenon," or the "Buried Secrets," you also included a lot of animation.

- Yeah.

- How do you pick who's going to animate the B roll if you will?

- Well, animation is a really important part of the storytelling, and particularly when you're dealing with, you know, - Historical?

- historical or engineering.

So like, you know, with the Parthenon to actually visualize what it had looked like, you know, animation plays a major part of that.

We've been working with mainly the one animation company called Hand Crank Productions.

- Where are they located?

- They're in just over the border in Massachusetts.

- Massachusetts.

Okay.

- One of the things, I first worked with them on "Bibles Buried Secrets," and one of the things that attracted me to them is they have this, they do a lot of stop frame animation.

And I thought for "Bibles Buried Secrets," I really wanted to create a physical Bible and fill it with the most beautiful art historical images from the Bible.

Like stories of Moses receiving the 10 Commandments, or you know, David with his slingshot against Goliath.

And I wanted it to be leather bound and gold leafed and all that.

And so we did that with Hand Cranked.

We actually produced a physical Bible and- - [Steven] One frame at a time.

- The concept was we were gonna have this archeologist table, and the Bible would be one of the things on it.

And so when we were accumulating all this evidence of the intersection between Bible stories and actual archeological evidence and extra, his extra biblical historical facts, we wanted a place for it to exist on a table.

But we wanted the Bible to actually feel physical because so many people have Bibles in their families that have been handed down for generations.

And it's, there's something visceral about it.

And at the time, I just didn't think that this was back in, what'd I say, 2008 or something.

- [Steven] Right, right.

- The digital technology just couldn't capture that kind of texture.

So we decided to do it in stop frame animation.

And so we had some, you know, so turning the Bible, the page of the Bible, and illuminating certain lines in it, some of those shots took 48 hours to do in stop frame animation.

But I maintain to this day that you can actually feel the texture of that bible.

- The tactile.

- Right through screen.

- I've had, Gary, I've had conversations sitting across from me, Doug Trumbull, who did the "2001," "Blade Runner," "Close Encounters."

And we talked about how miniatures often stand the test of time.

Joe Johnston, who's a good friend of mine, who did the "Star Wars" films, and created, designed a X-Wing fighter and the Star Destroy and all said the same thing about how these tactile, these actual physical miniatures stand the test of time because they are real.

- Yeah.

- And sometimes the digital we have our eyes become so educated that we see, man that is clearly a computer graphic that, you know, you look, it was something that might have been 10 years ago, and we clearly see that that does not seem real, but I agree with you that tactile thing still has power.

- Yeah.

Yeah.

And, you know, and I think you can make the same case for authentic storytelling, that you can tell when somebody is telling a story from their real experience, from their heart.

And, you know, that's something that I'm very proud of for the "Native America" series.

And, you know, it had to do with, I think, the connection between our filmmakers and the communities in which they were gathering stories.

- Yeah.

Now in 2009, you won Writer's Guild of America, best documentary for "Secrets of the Parthenon."

- Yes.

- Tell us about that.

How that started and what that meant to you.

- My mother's family is Greek, we're Greek Jews from a little place called Yanina up on the Albanian border.

- Yanina.

- Yanina.

And, you know, I grew up in a lot of, going to a lot of Greek diners, and I always see the Parthenon on the place mat or the mug.

And I thought, why is this considered, you know, a symbol of Western civilization?

And I thought I'd look into that.

And I was very fortunate to connect with some people who were actually in charge of restoring the Parthenon, or conserving it, I should say.

- Preserving it, right?

- Preserving it.

Yeah.

And so I connected with them and made that documentary about the Parthenon.

And it's one, still one of my favorites.

- What do you love about it?

Tell us something we don't know.

- Well, first it's- - What's one of the secrets of the Parthenon?

- Well, lemme tell you, there's no secrets.

(Steven laughing) There's no secrets.

When, you know, a show is called the "Secrets of the Parthenon," the Secrets of the Colosseum or whatever.

How did they build it without any, you know, computers and, you know, machines.

The secret is political will, you know, that people saw something that they thought was worth doing and they gathered their resources and did it.

And that's the secret of all those.

So if you're looking for secrets I just gave, you know, I just gave it away.

- It's having a vision and putting that vision into action.

- Exactly.

Exactly.

Well, the thing about the Parthenon is that it's more of a sculpture than a building.

Now, each stone in the Parthenon is individually carved and unique, and it's not just a Lego set.

And the reason they did it that way is because they built it for visual impact as opposed to, you know, mathematical precision.

- Like art.

- It's art.

So that when you're looking at it, it recognizes the way we see and how it almost looks like it has, it's like it's breathing itself.

It looks like it's holding its own weight.

It has a sort of a shape to it.

When you look at just the base of it, the center of it is higher than the edges.

And it has this effect of it being, looking perfect, but it's actually not geometrically perfect.

And it had to do with this idea that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, or man is the measure of all things.

And so it was more important that it looked a certain way as opposed to being, you know, a perfectly straight line.

- Hmm.

Amazing.

- How much time did you spend on that particular project?

Do you remember?

- Probably about a year.

- Yeah.

And how long did you spend filming there?

- We were there maybe three weeks.

- And do you know what you're getting before you get there?

Or is it, are you just kind of going with the flow?

- We do a lot of, you know, pre-interviews, making sure that we've, you know, found the right people to talk to and that they're willing to talk and give the amount of time that is needed to make a documentary, and that we have proper access and all that.

So there's a lot of pre-production and pre-planning.

And we, you know, map out the questions that we're gonna ask.

We have an idea of what the answers are going to be.

- Right.

- And, you know, have a pretty good idea of, we have a shooting script, we have a pretty good idea for something like that.

You know, what we're after- - Subject matter, particular specific area that you're asking as a professional.

- Yeah.

But you also have to be open to, you know, surprises and, you know, happy surprises.

- Yep.

When, you know, when we were talking in 1982, I remember for me, my graduation gift from high school.

You know, you could go on a trip or do this and that.

My gift I requested was a VHS recorder, so I could see my movies.

So you mentioned VHS.

How has your work changed as the industry has changed and the tools have changed?

How has your workflow changed?

- Well technology- - Including cameras and everything.

- Yeah.

Yeah.

I mean, the technology has just been, you know, incredible in terms of how it's changed.

You know, when I was doing my workshops in prison, you know, we had a VHS cuts only machine and an Omega computer that hooked into it.

So we could do some kinds of effects.

And today, you know, in our pockets, we have more production capabilities than, you know, we had back then.

- Right.

- Certainly first of all, workflow, you know, now I'm able to work with editors around the world.

And because of digital technology, we can all share the same media, digital media, we, you know, the "Native America" series could not have been done without Zoom and, you know, shared digital assets.

It's not quite like being in the same room, but it's the next best thing.

So just in terms of collaboration, the technology's helped a lot.

- And you've had to evolve as a filmmaker as well, right?

As far as learning these different technical aspects?

- Yeah, I mean, I was talking to my longtime composer yesterday, and we were reminiscing and he was saying that, you know, one of his favorite parts of "Native America" was the drone shots.

I mean, drones.

- Right.

- I mean, we used to, you know, I've gotten like balloons and filled them with helium and stuck cameras on them to try to get an overhead shot or.

- Right.

- You know, I remember we were doing something on The Big Dig and, you know, I asked if we could put our little digital camera on a crane and have it swing back and forth, and- - You're a helicopter?

- Helicopter.

But that's big budget stuff.

- Right, right.

- But now, you know, I mean, drone incredible.

- Yeah.

- What an incredible inNOVAtion.

- Let's talk about you, you mentioned your composer, and that was something I was gonna ask you about.

You're using this, you use the same composer primarily?

- Yes.

- He's your maestro.

- He's my maestro.

- Who is that?

- His name is Ed Tomney.

- Yep.

- And we met when we were, I think 17 years old in New York, and he had a punk band.

I would go see him at CBGBs, and we've been friends ever since.

And he's scored lots of films, and so I'm very fortunate that he's continued to score my documentaries.

- Wonderful.

What's next for Gary Glassman in Providence Pictures?

Anything you can share with us?

- Well, we're talking about season three of the "Native America."

And again, sort of pushing the- - The boundaries.

- Sort of the boundaries in terms of production.

One of the things that should come as no surprise, but, you know, we had six and a half million viewers on broadcast for the series.

We had- - Six and a half million viewers?

- Yeah.

We had about 200,000 streaming it, and we probably had 10 million, you know, sort of consuming social media along the way.

So I think being more conscious of integrating social media into the production process from a much earlier time and building audience, which now has become much more, less audience of just sort of like a one-way receivership and more of community where you're hearing back from the people that are watching what we're producing.

And so we have ideas about how to - Integrate.

- integrate that more from the very beginning.

- So you get, so that feedback is helping to create a new series in a way?

- Yeah.

- Like their desires or will you explore this?

Will you touch on that?

Is that- - Well, we get lots of sort of pitches, ideas, why don't you come here and do this?

- Right, right.

- All that, but more about a sense of almost ownership, feeling a part of the production.

And I think that's something that we wanna develop more.

- So social media has really expanded your audience base, you feel?

- I think so.

I think so.

And giving them an opportunity to feel like they're participating.

- Now, what makes you decide to do a BBC, or Discovery, or NOVA?

Are you pitching to all of them?

Or did they say, Gary, we love this.

What are you doing next?

How does that work?

- Well, some of it is just pure, it's just business.

- Yeah.

- And the early, like the whole "Building Wonders" series that was done in collaboration with NOVA PBS and Arte, which is the public broadcasting entity in France and Germany.

And when you have a subject that has international interest, it's more possible to get international investment in it.

So it's mainly necessity, but you have to start, usually you have to start with an American partner first.

- Yeah.

- An American broadcast partner first.

- Any words of wisdom you would share with anybody interested in creating documentaries, or starting a business, or anything you wanna.

- I would just say first of all, never let money stand in your way.

Again, as we said, you know, you have a whole production studio in your pocket on your phone.

So if you've got a strong idea, just do it.

Just make it, just make it happen.

And, you know, there's a lot to learn from just doing it.

And, you know, I think the professional development and the money and all that, you know, will follow.

- Yep.

And there's also power of mentorship too, right?

- Sure.

If you can work on a production, you know, try to work on a production, any kind of production, you know, you learn a lot from that.

It's funny, I see on social media, there's a movie "The Warriors," and it's sort of come around.

One of my native colleagues got me a T-shirt, that's "The Warriors."

It's a takeoff of the original Walter Hill films.

- Yeah.

♪ Warriors come out to play, yay ♪ - That's it.

That's it.

So, but the T-shirt has actual native warriors on it.

But my first production assistant job was on "The Warriors," Walter Hills.

- The Walter Hill?

Wow.

- Yeah, yeah, yeah.

- That's funny.

- But there I was, I mean, you know, basically crowd control, you know, making sure that the actual gang members who they had hired as extras were only taking one soda at a time.

(Steven laughing) That was my first job.

But there I was, you know, on set in this incredible production that's become sort of a cult.

- It is a cult film, right?

- Yeah.

- That was a big to do.

- Yeah.

- Well, Gary, I want to thank you so much for taking the time outta your busy schedule to join us on "doubleFEATURE".

I want to thank you for your talent and friendship, your leadership in the community.

And you are a Rhode Island treasure.

A cinema treasure, treasure, treasure.

So thank you so much for being on, and- - Thank you Steven.

Thanks for having me.

- We really appreciate it.

(upbeat music)

The Legacy of George T. Marshall

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 58s | Remembering the founder of Flickers, George T. Marshall. (44m 58s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 59s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, writer, and actor, Tom DeNucci. (44m 59s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 2s | Interview with Alex Berard. (45m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 59s | Steven Feinberg interviews First AD, Emma Barber. (44m 59s)

Interview with Chad Verdi Jr. and Paul Luba

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 31s | DoubleFeature shows films from around the world and takes viewers behind the scenes. (45m 31s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 41m 15s | DoubleFeature shows films from around the world and takes viewers behind the scenes. (41m 15s)

Interview with Angela Peri and Lisa Lobel

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 25s | Interview with Angela Peri and Lisa Lobel (45m 25s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 45s | Interview with Jerry Ketchem. (45m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 49m 15s | Steven Feinberg interviews award-winning filmmaker, Elyse Katz. (49m 15s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 30s | Steven Feinberg interviews storyboard artist, Martin L. Mercer. (44m 30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 19s | Steven Feinberg interviews Providence Pictures' Gary Glassman. (45m 19s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 40m 24s | Steven Feinberg interviews producer Erika Hampson. (40m 24s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 41m 56s | Steven Feinberg interviews directer/producer Joe Johnston. (41m 56s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 29s | Steven Feinberg interviews producer David Crockett. (45m 29s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 42m 44s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview the late film director, Douglas Trumbull. (42m 44s)

Henry Bronchtein Interview Pt. 3

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 15m 25s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, producer, and production manager Henry Bronchtein. (15m 25s)

Henry Bronchtein Interview Pt. 2

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 14m 51s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, producer, and production manager Henry Bronchtein. (14m 51s)

Henry Bronchtein Interview Pt. 1

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 15m 33s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, producer, and production manager Henry Bronchtein. (15m 33s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 37m 9s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview producer and writer, Roger Lyons. (37m 9s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 27m 31s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview filmmaker Dante Bellini. (27m 31s)

Katie Reaves and Jennifer Jolicoeur Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 27m 7s | Interview with filmmaker Katie Reaves & Athena’s Home Novelties Pres. Jennifer Jolicoeur. (27m 7s)

Dr. Thomas Zorabedian Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 27m 6s | Steven Feinberg interviews professor and video producer/writer, Dr. Thomas Zorabedian. (27m 6s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 47s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview picture editor Rob Schulbaum. (26m 47s)

Ron Bachman and Devin Karambelas Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 45s | Steven Feinberg interviews Ron Bachman and Devin Karambelas from WGBH in Boston. (26m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 15s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview filmmaker Eric Latek. (26m 15s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 51s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview host of Conducting Conversations, Mike Maino. (26m 51s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 6m 34s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview actress, producer, and screenwriter Marlyn Mason. (6m 34s)

Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 16m 5s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview author Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel. (16m 5s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 51s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview director Alexia Kosmidor. (26m 51s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

doubleFEATURE is a local public television program presented by Rhode Island PBS