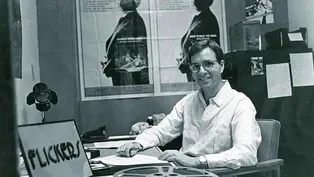

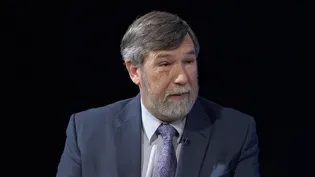

Interview with Jerry Ketchem

Clip | 45m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Interview with Jerry Ketchem.

Steven Feinberg Executive Director of the RI Film and TV Office interviews Jerry Ketchem, who was served for the past 25 years as Senior Vice President of Production at Walt Disney Studios.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

doubleFEATURE is a local public television program presented by Rhode Island PBS

Interview with Jerry Ketchem

Clip | 45m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Steven Feinberg Executive Director of the RI Film and TV Office interviews Jerry Ketchem, who was served for the past 25 years as Senior Vice President of Production at Walt Disney Studios.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch doubleFEATURE

doubleFEATURE is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(gentle music) - Hi, I'm Steven Feinberg, executive director of the Rhode Island Film and Television Office.

Our guest tonight is Jerry Ketcham.

He's been the senior vice president of production at Walt Disney Studio since 1994.

I met him in about 2005.

He's done amazing work, and I wanna welcome Jerry to "doubleFEATURE," welcome, Jer.

- Thank you, Steven.

It's a pleasure to be here.

Thank you for inviting me.

- And you're in Los Angeles right now.

I know you've been busy working on all kinds of productions.

And you and I met, I think it was 2005, on the Walt Disney production of "Underdog."

- Correct, yeah, I remember we were kind of finding the right city to do it, and you approached me and said, "Hey, come to Rhode Island.

We have a armory that would be available for you for a stage" 'cause obviously a very important factor to make a movie is a stage set.

Came down and saw the Armory, shook hands, walked around with the director, and that's how it all started.

- And we were filming at the State House in Rhode Island.

We turned Providence into Capital City, and I think you guys spent the entire summer at the Rhode Island State House.

- Yep, we did.

And the governor at the time was very generous, allowing us to kinda lock off all the corridors and use his lawn, and he was very excited to see us 'cause we had a lot of employment happening and a lot of extras running on the lawn when there was a big scene that involved a big crowd.

So it was a good, good experience, I hope, for all.

- It was a lot of fun.

It was a lot of fun.

We still have the little kids that go around the State House saying, "Oh," well, actually, it's now their parents are taking the little kids and say, "This is where 'Underdog' happened."

- Yeah, that was a perfect setting.

- Jerry, you started as the senior vice president of production at Disney Studios in 1994.

- Correct.

- That's a lotta productions.

Now, how did you start getting involved in the business originally?

Did you always wanna do film and television production?

Was that an interest when you were younger?

- No, to be honest, my parents gave me encouragement to become an accountant, to, you know, be available to work anywhere and almost any company, so I started doing courses in that in New Jersey at a community college, County College of Morris.

And then, about after the two years of time to graduate, I ran into somebody who went to University of Florida and was telling me how exciting the broadcast journalism school was.

I went down to Florida, transferred, kind of got really excited about that, and then a film course that was part of the curriculum, making small movies.

I made a short with my friends around the campus, and I got to edit it, and just a very small shoot.

Three or four days, I think, we did it in, and, you know, I got the bug, so I moved out to Hollywood in '76, so that's a long time ago.

- Wow.

- And got into the business right away.

And a big break I got was doing location scouting, and then I was noticed by Burt Reynolds' company to start working with him, and if any of your audience doesn't know, he was a really big movie star in the '70s.

- The number one.

He was the number one film star in the world.

I mean, so the "Smokey and the Bandit" movies, and you worked on what, "Smokey and the Bandit II", and "Sharky's Machine"- - Mm-hmm.

- and "Stroker Ace."

Those were all the Burt Reynolds.

And he had done "The Cannonball Runs" movies before that.

- Yeah, I did eight movies with Burt- - Wow.

- and then a TV series called "Stroker Ace" in West Palm Beach, and then he got into television more.

"Evening Shade," it was called.

- Right, right.

- And when he got into that, that was kind of an area of the business that I wasn't interested in.

I enjoyed practical location shooting, so I moved on from there, but what a boost to my career.

- Good for you.

I mean, so you were thinking about being an accountant, then you started making films, then you started doing locations.

Did you have any mentors at that time?

- I would say Burt sort of in that doing location scouting.

He directed "Sharky's Machine" and noticed that, you know, I really had a good instinct for production, so he said, you know, and I helped, you know, the assistant director department get him out of his trailers.

And one day I, you know, knocked on his door and gave his 10 minutes, which he always asked for to get hisself ready for the shot.

Some people rushed him to the set, and he liked that I was calm about it, so he said, "I gotta get you in the Directors Guild, so you're the one that gets me outta the trailer."

And I said, "Burt, that's quite a deal, quite a deal.

It takes years to get in the Directors Guild."

And he said, "I have good lawyers."

- Ah.

- So we figured it out back in LA, and in very short order, I became an assistant director, you know, and I owe it all to him.

- What a great, see now, you were really useful.

You always carry yourself in such a pleasant way.

I'm not surprised that he noticed that, and how, you know, you're always responsible, and you do such a great job, and I'm not surprised he gave you that kind of help.

And so, when you became the assistant director in the Directors Guild, did you then take on that position for subsequent films?

- Yes, I didn't look back to locations again because all of a sudden, I was dealing just with movie people, which, you know, a lot of your audience would understand, some don't.

It's we change our minds a lot.

A very friendly group and professional, but we're moving with weather and script changes, and so I, as assistant director, you're just dealing with movie people, and when you're a locations manager, you're most often dealing with the communities, and some people, they don't always understand how we change frequently.

- Right.

- So I was happy to become an assistant director, and a couple of movies with Burt as an assistant director helped me get into Universal Studios, and I started doing back-to-back shows there, episodic television.

I landed into Steven Spielberg camp, doing "Amazing Stories" in '85.

- Right.

- And I got to work with a lot of directors.

And Steven, of course, directed a couple of them, and that again helped me with experience in the movie business running sets.

- [Steven] And that was- - And that's how I kinda moved up.

- That show was the show everybody was looking forward to.

I think his episode was "The Mission," right?

That was with Kevin Costner.

- Mm-hmm.

- And then he had all of these different directors.

It was that anthology series, like the idea of "The Twilight Zone" and "Outer Limits," and these were these fantastic shows, and I remember he wanted, I happened to be working with that casting company, Mike Fenton at that time, and he wanted to have really great actors, and he had fabulous directors, so you had a different director every week.

- Yeah, and, you know, Clint Eastwood, Martin Scorsese.

I mean, after every seven or eight days, Steven, Bob Zemeckis, and a lot of up-and-comers, that was Steven's approach.

The very seasoned pros and bringing people from, you know, Lesli Glatter was one who's now doing major television, is the president of the Directors Guild of America.

She was brand new, did her first episode.

And Todd Holland, another director that's done quite well in television.

And so, again, just, it's networking is a huge part of our business.

And then I got an offer to go into the studio in '94, and going back to one of my first jobs when I moved on to do Burt Reynolds' movies, I moved on from an afterschool special company, and I replaced myself with Bruce Hendricks, who was the president of Disney production, and when he got the job as president, he said, "Why don't you come inside and, you know, work with me on movies?"

Didn't wanna do it at first, but here I am.

- Why didn't you?

Why didn't you wanna do it?

Why didn't you wanna do it?

- It just felt like when studio executives came to sets, it was all about what was not working well on your movies as opposed to, hey, your dailies were great.

And running a movie set and being involved with getting a great shot and setting the background, and making your day being at the director's side was always something that really fueled me.

And going to meetings and, you know, being very corporate didn't seem like what I was looking for.

I always would tell people, you know, before Disney, of course, "I'm no 30 year, you know, guy to get a gold watch," and guess what?

This March is 30 years.

(Steven laughing) - So let me ask you, when you were the assistant director, which is basically being the right-hand man for the director, and you're verbalizing his needs or her needs, right, to the- - Mm-hmm.

- rest of the crew, and you're also kind of keeping things moving, right?

Wouldn't that be a good description of what you were doing?

- Yeah, I mean, you plan the show.

You know, what's actor's schedules, and you incorporate a schedule.

It could be whatever number of days, 20 up to 85 or more shooting days.

You organize the days, and, as you say, the director and you and the cameraman, and they sit down, and you plan out each week, each day, and each week, and you try to communicate that to the crew, so we're always ahead of the shots.

We're always a couple days ahead of what we have to be prepared to do.

Maybe there's lighting to be done ahead of time.

It takes days, so we would, you know, just indicate to the Electric Department, Grip Department that, okay, we're gonna be shooting there on Tuesday, so maybe the Thursday before they start rigging so they're ready on Tuesday.

We move in and start doing our work.

- Yep, and do you have to be a policeman at some point, where you have to say, "Guys, we're behind," and you have to crack the whip?

- Well, you do, but I think a style that I've always had was just let everybody know what we have to do to get back on schedule, including letting the director know if we're not here by two o'clock in the afternoon on a shot, we're not gonna make our day, and then we just try to maybe drop a setup or two in a scene, so we're just doing wide and closeups as opposed to a lot of coverage.

Not a crane move, but something more stable that'll move faster.

So you're right, the part of the job is just to try to keep your day on schedule so at the end of the day, you can know that you've done a great day's work.

We only shoot, by the way, in features anyway, about two minutes a day of the screen time, so.

- It's funny, well, that's for a studio film, right?

That's for a studio.

- Yes.

TV can be- - Because I was talking to my friend who's directing an independent film, and he has to do like eight or nine pages a day.

- Yeah, that reminds me of my episodic days when you're just, you know, if somebody stumbles their lines, all of a sudden, you say that's an affliction that that character has.

You don't have a chance to even do extra takes.

- When you were doing, when you were doing the "Amazing Stories" and television, were you using one camera or two cameras?

Do you remember?

- We would usually use one.

Two kinda came in later on, but we'd always have a backup B camera in case we needed it.

And so, you know, they'd stay off and get inserts, small shots, while the first unit would move on, but the two cameras kinda came into play probably in the '90s- - Yep.

- where it was every day.

- And it seems like that's the norm now for television, right?

- Yes.

Yeah, and Ridley Scott, a famous director, he uses up to five at a time.

- Does he really?

- Yeah.

- Have you worked with Ridley?

- Only when he was a producer in a couple movies we didn't make, some conversations.

He's quite a remarkable man, but not directly on a movie that got made.

- Yeah, so you also did a film, "Dreamscape," right?

Didn't you work on "Dreamscape?"

- Yeah, that was my first official job as an assistant director.

You know, I did locations.

When they hired me, they said, "You know, we want you to do locations."

I said, "I'm an assistant director now, so I'll tell you what, and if you hire me and give me that credit, I will help the assistant directors when I can," but I want to start be known to the, you know, different hiring companies that I was now an assistant director, so that's how I got that first job.

- Boy, oh, boy, Burt taught you well, man.

Burt taught you well.

So, all right, so now you're at, let's say, now you start at Disney in 1994.

You're the head of, or the senior vice president of production.

What was the first film you worked on for Disney?

- The first one was called "Man of the House."

It was Chevy Chase and Jonathan Taylor Thomas who if people remember him from the Tim Allen show.

- [Steven] Right, right.

- That he was the young boy in the family, and it was shot with Farrah Fawcett and Chevy Chase up in Vancouver, so that was my very first movie for Disney.

- So as the senior vice president, you find yourself traveling quite a bit?

I mean, obviously, you came to Rhode Island when we filmed in Rhode Island.

I know you just mentioned Vancouver.

You've done films, "Jungle Book," "Jungle Cruise," "Snow Dogs."

I mean, are you having to travel a lot in your position?

- Yeah, and it's exciting part of my job and why I enjoyed it so much for all these years.

When we first do a movie, I've probably done over 135 just for Disney.

- [Steven] Wow.

- And so about five a year or something, it's four or five.

And my first part of the job is to try to find out where to make the movie, so I usually try to have one or two options, present it to the director and his producing team why I think it's right for the movie.

And then, we go on a scout, and as we did on "Hocus Pocus"- - [Steven] Two.

- in your state, I traveled there with Anne Fletcher and Lynn Harris, producer and director, and then we kind of walked the streets and tried to, you know, kinda, you know, kind of vision the story, certain scenes, where we play it.

As you know, we ended up in Newport for quite a few scenes, a couple of other towns, and then we ended up in Providence for several and used your Armory for the woods in the movie.

So I enjoy that, being part of that decision process.

We didn't even go to another state.

We said, yep, this works, so.

- And we turned a farm, Chase Farm in Lincoln, into a 1600s Salem Village.

- [Jerry] Yes.

- [Steven] Did you know you were going to do that in the beginning, that you were going to create the Salem Village?

- Well, you know, yes.

I mean, I thought maybe we'd go up to Salem and shoot plates and maybe do a one cabin, you know, in Rhode Island.

But as it turned out, the vision of the director was, you know, bigger shots, and we were able to, within the budget that we had, build the village that you mentioned and that way, we could also shoot interior and exterior as opposed to plates, which are, for the audience, just a background.

You know, you can't really walk into a plate.

It would just be a backing.

So we were able to go in and out of the film inside those huts, et cetera.

And it was the opening of the movie, and it really helped open up that we had a big story to tell.

- And it really established, and on those early days, it was drizzly and muddy, and you really felt like you were in the 1600s Salem, and you had farm animals there.

I mean, you guys do it so well.

I mean, it was beautiful.

And then we had worked with Anne previously on a movie called "27 Dresses" with Katherine Heigl, and I think she had a positive experience here before, so I was glad that we were able to work with you again on that.

You know, so much has changed, Jerry, when you started out in 1994.

With the evolution of film, the incorporation of so much CGI with the practical green screen, all this stuff going on, and you've overseen projects like with "Pirates of the Caribbean," "The Lion King," can you talk a little bit about how things have changed for you as a production person overseeing all this stuff, and maybe how much do you have to now spend in the budget that's special effects-driven?

Can you talk about that?

- Well, again, every project can be different.

I know that I grew up as a filmmaker.

Yeah, I mentioned locations and assistant directing, shooting practical locations meaning real places, real homes, real restaurants, city streets, and now, in the world of computer-generated imaging, we can create a lot of that just with a little piece of set.

And if folks see "Jungle Cruise," a movie we shot in Atlanta, and we were in England at the end of the movie, a beautiful street in England, well, we only built one building, and that's where Emily Blunt and Dwayne Johnson were for the scene, and then when they pulled out, and the end of the movie happened, all of that was created on a computer with cars and people walking and what have you.

So that is, you know, advancing every year.

We talked about "Amazing Stories" back in '85.

That was right when green screen was kinda coming out.

We were having to, you know, stabilize the cameras, and it took almost a half a day to get one shot.

Now, we can throw up a green screen and grab something in less than an hour, and which is where we would put, you know, the image in.

But to answer your question, you know, Marvel movies, which I'm not part of, but if you look at any behind-the-scenes work they do, they're primarily on stage creating a lotta the action in a controlled environment, and then putting in there, certainly, otherworldly backgrounds through CGI, and it's looking so good now that it's almost like you were really there.

- It's unbelievable.

I was talking, we had Doug Trumbull here who did "2001: A Space Odyssey" and "Blade Runner," and we were talking about the difference between the physical miniatures as an example and CGI, and he said, "What's surprising is a lotta the miniatures stand the test of time because they're physical.

You can touch them.

And sometimes, the computer graphics don't stand the test of time because either our eye, we're educated, our eyes are educated, and so it becomes more and more advanced as it goes along."

Have you looked back on some of the older films and said, "Oh, boy, it would look a lot better," you know, maybe it was 10 years ago, and there's a difference?

- Yeah, I mean, when I do research on doing a movie, you mentioned our TVs today are so high-def, definition, versus, say, "Pete's Dragon," a movie we remade in New Zealand.

- Oh, right.

- I went and watched the first one, but on my TV, I could see through the dragon, you know?

- Oh, right.

- It was forgiving back in the day with the TV sets we had.

And it was interesting, I just saw yesterday a miniature from "Star Wars" sold for over $3 million at auction- - Yes.

- they found in the creator's garage, you know, undercover.

They didn't even know it existed.

But I've seen in my day, not that I worked on "Lord of the Rings," but I was in New Zealand, the producer gave me a tour of their studio, and to see all of those castles done.

And you could walk right up to 'em, the detail on them, and it's really just wonderful to watch them.

But today, we'd probably do that on a computer because, again, the resolution has gotten so good, and we might shoot different elements that are real and put them together to create a castle or a unique environment.

- When you get a project, you know, whatever the project, let's just call it, whatever, let's just call it "The Dragon."

When you get a project, are you the one who is going over and creating a budget, or are you hiring someone to do the budget?

There's a studio, someone else in finance saying, "Jerry, this is the budget you have to deal with, and you work it out."

What's the process if we were gonna do a movie called "Dragon?"

Someone somehow says, "Disney's doing 'Dragon.'"

What are the steps for that?

- Well, I, you know, am point person first from the creative.

The script would come to me, and I'd read it for entertainment, one, first, and then I read it every line by line on where we would make the movie.

I would try to look at what services the story.

If it's a dragon movie, it's likely, you know, Ireland, you know, kind of rolling hills and what have you.

It depends on the era the dragon is in.

If it's comes out of the past into the present, then that would be- - Just know- - a whole- - that we have dragons here in Rhode Island, so if you're ever doing a dragon movie, just come to Rhode Island.

- South, South Rhode Island, I believe, yeah.

So, and then the incentives, which again, not everybody's familiar with, but states, countries have created incentives, and your state was one of the earlier adopters back in early 2000 to attract us because we're a clean industry.

We create a lotta jobs.

We use local hardware stores, dry cleaners, restaurants, a lot of our crew comes in from the outside.

We eat at the restaurants.

We fill up hotels.

Our crews are probably 150 to 300 people, depending on the phase of your movie.

If you're constructing, you have a lot of carpenters.

Hire as much local as possible, employees.

So we're attractive in that respect.

So in addition to servicing the story, we look at incentives, and then we look at, you know, the time of year.

Weather, you know, I'd have to take that into consideration.

They wanna make a movie, you know, say, in the summer, but it's a winter movie, then I'd say we need to go south of the equator when they're having their winters and just the opposite.

You know, if they want to be shooting in March, you know, for summer, I'd be going down there for their summers.

So I have to take weather and that.

And then we have internal accounting staff that looks at other movies that have been made.

Most movies are similar to other movies, and we might go to another studio and say, "Geez, you just worked in, say, Bulgaria or Ireland, United Kingdom, on a movie that seems similar.

Can we see your budget for what you're paying crew rates, stage rates, et cetera?"

And we'll put together a budget internally, and then once we have filmmakers on, get their involvement on specific locations so we can then be more specific how that money is spent.

The studio does what they call a P&L, profit and loss, and they look at a movie and the movie star that you plan to put in it, and then they project how much they get in return at the box office based on the kinda movie it is, and they'll give me a budget number to try to hit, and I do my best to get to that number, but I often, you know, have to let them know that, geez, you're several million short.

And not always, but when I do, and they'll say, "Okay, what can we do to get that back to budget?"

And I'll give them suggestions, whether it's eliminate a location in the movie and try to do more in different, you know, so we're only in a few spots, and then we work back and forth.

Our prep on a movie, again, mentioned "Hocus Pocus," the most recent one I did in Rhode Island, I think we had, you know, about four months to plan it and build the sets, et cetera, maybe a little bit longer.

And so we worked back and forth to try to, you know, keep to that number, keep to that number, and then if we can't get to the number, it's my job to explain why to the senior executives at our studio why the number that I have to make it is not sufficient, and the movie you want, here's the number.

And then if I'm convincing enough, I'll get that extra money, and the studio will take a chance that the returns will be, you know, because it's gonna be that much better, it will get our money back.

- Do you deal directly with the director and the producer on a feature film, and will they be the one trying to convince you, and then you have to go and convince the rest of the financial folks at the studio?

- Yeah, that's kind of how, or the director will say, "Geez, I just have to, you know, do this scene in, you know, Hawaii," say, "even though the rest of the movie's in another location."

So I will try to come up with ideas if they haven't already, of how about if we just send a second unit with doubles and get everything we need.

"Eight Below" is a movie we did, Frank Marshall directing, and we couldn't afford to go to Iceland for these beautiful locations, so Frank, it was his idea, actually, let's go to Iceland with a second unit, and we'll put the hood up on the actor, so you can't really tell who it is, and then we will come back to Canada and the hood will come down, we'll know it's our movie star.

And then we were able to save, you know, unbelievable amount of money not sending the whole unit to Iceland.

- Right, right, right.

Jerry, in the many years that you've been working at, and you said 30?

Congratulations on that.

- [Jerry] At Disney, yeah.

- 30, do you have any favorite films that you've worked on?

And if so, can you tell us why they were favorite films of yours?

- Well, you know, I'd say it's always the one I'm working on now, you know, 'cause I try to approach every movie with that potential enthusiasm that it's gonna be the best ever.

But believe it or not, a very seldom seen movie called "Bubble Boy."

I had a lot of fun making that.

It was Jake Gyllenhaal's first movie, I believe.

Just because it was different Disney, you know?

I mean, it was so kind of on the edge of a dark comedy, but so many movies.

I mentioned 135.

They've all had something really special about them.

Sometimes, the bigger budget, bigger movie star movies aren't as much fun as the smaller ones that are more flexible, and you're moving, you know, on your feet, and you're moving a little bit quicker.

But, you know, there's a wide range of them, but I would say, you know, I think "Hocus Pocus," again, was a lot of fun to work on, hanging out in Rhode Island.

I came back a few times.

I enjoyed being there.

And Massachusetts, we made a few movies.

"Godmothered" was the last one I made there- - [Steven] Right.

- so another wonderful place to make movies.

So it's hard to pick out one because they're like my children, you know?

I like them all.

- I will tell you that I get approached at least weekly, "Steve, are they gonna make 'Hocus Pocus 3,' and can they make it here?"

So just, I'm putting the plug in.

Everyone in Rhode Island.

- Well, I will say that, as you know, we had a writer's strike for a long time.

- Yep.

- That was settled a couple of weeks ago, and they are back into writing another sequel, "Hocus Pocus 3."

And I haven't read it yet, so I don't know if the ladies are still in Salem, which is the setting- - Salem.

- for the movie, even though we shot it in Rhode Island, so I will probably get that script, I'm thinking first of the year.

- Oh, good, well, if they're not in Salem, maybe they'll come to Providence.

- There you go.

(Jerry and Steven laughing) - What about, this is kind of something that's happened in the last few years quite a bit, where you've taken animated films, and now they've become live-action films.

How has that been?

What's that experience been like?

What are some of the challenges that you're facing as the head of production at Disney?

- Well, I think the challenges are, you know, in animation, they can really, you know, they're working in computers and drawings.

They don't do too much of 2D artwork anymore, mostly 3D computer, is just the universe that they create is so wonderful.

The first one I did, and I've done several of them, was "Cinderella."

- Oh.

- And Ken Branagh was our director, is also a famous actor, and he said, "You know, this is how I envision the movie," pretty much like the movie itself.

And we cast the movie with Lily James as Cinderella and tried to follow true to what the fans so love about the movie in animated form, and we had a lotta success with it, and we just, you know, stepped up our budgets to make sure the world we created in the CG that's now capable of making it even bigger.

The ballroom was actually a practical set except for the ceiling, if you remember that beautiful scene.

- Yeah, yeah.

- And that was an amazing set to build in London at the biggest stage they have in London, in Europe, I believe.

And then we, you know, just chose to build the back lot town that Cinderella went to.

And the success of that led to "Beauty and the Beast" that we did.

- Did you oversee- - The challenges- - "Beauty and the Beast?"

- that there were was just making the Beast as wonderful looking and as nimble at being eight feet tall as it was in the animated film.

- And you oversaw "Beauty and the Beast," right?

- Mm-hmm.

- And that was Emma Watson, right, it was?

- Yes, yes.

And she, you know- - That, beautiful.

Beautiful film.

- Beautiful film, and she did a wonderful job, and we created the Beast.

We tried to do it real, you know, a man in a suit, but he was awkward on stilts, those type of shoes, or that was lifting him that high, so we created it in the computer with an actor who acted it all out across from Emma and then created the Beast.

I'm currently working on a live-action "Moana" with Dwayne Johnson.

We are in the earliest stages, still trying to figure out how to make that movie 'cause it wasn't that long ago.

It's one of the most watched animated movies on the Disney streaming service, and the fans just love it, so we're gonna be very true.

Again, we have some new scenes that we're putting in it, and Dwayne, as you know, played Maui in the animated film, and he's back, and we're just trying to figure out, again, the challenges are Dwayne has tattoos, and in the movie, they're different tattoos, and they move to music, so we have to figure out how to make that happen practically.

We have, I think, figured it out, but until the actors come back from their strike, we can't really work with actors to make sure that our idea works.

- And will you film that on location, or will that be more in a green screens type of situation?

- We're still figuring that out, but I would say because the fans of the movie, the water is part of the scene, how it moves and the beauty of it, the blueness of it, the clarity, how it interacts with the actors, so I would say quite a bit of it will on stage, but we just haven't got it all nailed down.

And there are some exteriors that we would do outside the village where Moana is in the opening of the movie and gets back to at the end of the movie.

We would build that as a practical location, kind of similar to what we did on "Hocus Pocus," that type of a village.

- Right, are you excited when you see a film, maybe like an "Avatar," or when you're doing "Little Mermaid," and, you know, you're seeing the advancements of the CGI, whether it's water.

I remember way back when, and they were starting to deal with CGI, and they were talking about hair and how hair didn't look like hair, and then it took a while.

But are you noticing those advancements, and is it giving you more and more comfort as you're in the actual production phase?

- Yeah, it gives me comfort, too.

Back on the first "Tron" movie, we created a younger Jeff Bridges, and we were lucky enough because creating younger Jeff Bridges, and it's a computer image, so we were able to get away with it not having the skin tone and the textures correct.

But now, to keep actors safe, we're able to do, you know, replicate actors.

So when they do a stunt, you can do it almost face on, either put their head on a stunt performer or create a total CG body, and you'd have to, you know, be related to the person to know that we didn't use the real person in a stunt.

- [Steven] Really?

- And again, it's a technology that's making our business safer, and I think the shots are even better because we can keep more of the actor that's the star of the movie in frame.

- Yeah, like, when you're doing "Beauty and the Beast," and you said you had an actor that's opposite Emma Watson, is that someone who's in like this green leotard with the dots all over them?

- Yes, yeah, and, you know, it's different technologies.

We used one called MOVA back then, and they have the dots on their face where cheeks go up, so when they're emoting, we are able to capture that, and then the computer can animate over it.

- [Steven] Yeah, wow.

- And so the performance is done that way.

And, you know, that's just, you know, again, enabling the actor to be against Emma, and then we have the director who actually is looking often at a monitor with the animated version just roughed in so they can feel the connection 'cause it's really about the eyes in these characters, so you really wanna get the depth of their eyes in the shot, and we do capture that and try to move that into the animated character.

- Yeah, what are some of the biggest challenges that you're facing when you're doing these large-scale productions?

And they're all, I'm sure, very different, but are there certain challenges that you're having to face on a daily basis or weekly basis?

- I would think the challenges are getting to a budget number.

These days, coming out of the pandemic, getting people back to the theaters, you have to wow them, or they would be satisfied with some really top-end streaming content on various streaming and network shows that have just come so far, and people have sometimes, you know, 60, 70, 80-inch screens at home that are like little movie theaters, so we have to satisfy the bigness of our movies, and but getting the prices down.

I mentioned incentives earlier, trying to be creative in other areas to get the budget number down.

That's probably the biggest hurdle is getting to the number 'cause we can almost today figure out everything else.

- [Steven] Right.

- You know, and we try to, you know, satisfy talent.

We're sharing actors all the time with other shows that are in the course of our production.

Some challenges of trying to keep them in our movie and then give them back to another series where they do a couple days on their episode and then come back to us.

Working with other companies sometimes to make sure they don't change the look of their hair or shave their beard if we have a beard in our movie.

So it's just like I say, it's ongoing.

Something a little bit different.

That's why I like my job.

It's something kinda different all the time.

I usually have three or four at one time- - [Steven] Oh.

- and I try to spend a little bit of time on each project a day, looking at what's most important on each project.

If I only have a couple of hours, what's the next thing that we have to get past to move it forward to camera.

- Do you look at dailies?

- We do, I have the capability of seeing it on my computer at home, and then once a week, we have somebody edit to see highlights of all the shows we're working on, and as a group, we do a group Zoom and hope to get back to doing it in a room, but we see like maybe a half an hour of each of our productions, what someone thinks is the best shots of that week.

- Yeah, do you get involved at all in the script process where you might offer some comments on a script early on that is just creative?

- Typically, it comes from how we can do something to make it better, you know, financially.

- Okay.

- "Wild Hogs" is an example.

It was written for Colorado, from Florida to Colorado, and I said, "You know there's no," again, "incentive in Colorado.

Could we write it for New Mexico?"

And, you know, that's not creative except that it changed the setting of the movie, and I went to New Mexico with the director and writer, and we came up with areas to make an exciting journey for the movie.

And so I would say, typically, that's how I get involved with the script.

If I have a creative idea, I might do it in the hallway or kitchen.

Never in a meeting do I want credit or blame (laughing) for an idea.

- Right, right.

Now let me ask you this.

You know, there are those big films that are magic films.

What was it like doing, did you work on "Saving Mr. Banks," a very different type of... - Mm-hmm.

- [Steven] What was that like?

That was a very different kind of movie.

- Well, we shot it in Los Angeles.

Obviously, our studio's in the movie, and, you know, working- - Tom Hanks - with Tom Hanks.

- is Walt Disney, right?

- Yep, and, you know, and Emma Thompson.

So it was just a wonderful experience going down to the theme park, Disneyland.

We shot on Main Street, but, again, it's Disneyland is about the guests' entertainment not being affected, so we had to be there at first light of the day, so we had from six until eight to shoot in the morning, and the park opened, and we were gone.

And so working with our own company's theme park, I mean, it was a positive experience, but complicated.

- [Steven] Right.

- And getting over to the carousel in the movie.

They did let us go there after the park opened for a couple of quick shots, but it was something a lot of people enjoy seeing is behind the scenes, seeing Tom Hanks, and, you know, Emma excited them as well, so we might've been able to be back at that area another hour and then we were gone.

But, and we- - Did you also film on the lot?

Did you film on the studio?

- We filmed on the lot in the movie 'cause our lot hasn't changed.

Part of Walt Disney's will was that we wouldn't change the look of the lot, and I thought very smart because there'd probably be high rises there if he didn't.

- Right.

- Other than Team Disney at our lot that was added later on, almost everything else is original.

You mentioned Ink and Paint earlier.

That building is not used for that, obviously, but the building is the same, and we didn't have to do much.

- Goofy Drive-In.

- And so- - You've got all, it feels like you're back in the 1950s.

- Yeah, I saw pictures, research of what it looked like, and except for the trees being a lot taller, it looked just like it did, you know, like in the '50s when we were creating the movie's story, and it was just nice to be in Los Angeles to shoot, and working with Tom and Emma was a real pleasure.

- When you're working on a film that you know is getting, or maybe you don't know if a film is getting a theatrical release versus a streaming, are there films that maybe you were anticipating getting streaming, and then they turn out another way, and they said, "You know what, let's go theatrical," or does it happen the other way around, or is that completely locked?

This is it, it's gonna be streaming or theatrical.

We're not gonna deviate from that.

- Well, I think because of the budget levels of most of our theatricals, we know when we start off it's theatrical.

But you're right.

Some of the streaming movies, you know, I think, in hindsight, "Hocus Pocus" would've been a good theatrical.

- [Steven] Yes.

- We made it for streaming, and, you know, when our lawyers make deals with the actresses involved, all of the talent, they're made for one use or another, and so it would've been complicated after we saw the movie, and I was at a test screening, and the people, you know, when we were previewing it, it was like it was a theatrical.

It was amazing how they interacted with the screen.

They were cheering, stood up after one of the songs.

- [Steven] Yeah.

- And we knew it should've been theatrical at that point, but we knew we didn't have the time to convert the contracts a certain way,- - Aw.

- and we'd already advertised it as an exclusive on our Disney+ channel, but I think Disney is looking at "Hocus Pocus 3" as a theatrical first.

- [Steven] Right.

- And so now we are more dedicating our movies upfront theatrical and then going to streaming as opposed to dedicating it straight to streaming.

There's still some of that, but I would say for our group, TV series will always go there 'cause they're not, you know, able to make a series for a theatrical, but I would say for the movies I work on, they're gonna likely be theatrical, and then a couple of other windows and then go to D+.

- I think that's smart because I also think that when you have that theatrical release, and it gets all of those eyeballs at the theater, it adds value to the film, so then when it does go to streaming, it's got a different feel because it was at the...

I remember calling you about that movie "Prey," "The Predator" sequel, which I thought, man, that should've been at the theater.

I would've liked to have seen at the theater.

- Same.

That's something that we'll look at again in the future of doing that theatrical.

And it has more awareness because it's been out in the theaters.

Advertising dollars are bigger for theatrical than streaming, so when it does go on streaming, people will go, "Oh, yeah, unfortunately, I couldn't go to the theater to see it.

I can't wait to see it."

Because now it's hard with so much content being made to get people aware of your movie, so that's how we expect to get more people watching them.

- We only have about a minute left, but is there anything you think will innovate the filming experience in the near future?

You know, we've had like 3D and things of that nature make it more immersive.

Do you think there's anything coming up in the next few years?

- Well, I'm gonna go to the dome in Las Vegas- - Oh.

- and take a look at that surround visual.

- Yes.

- And I think that, you know, we're always working on getting our movies to be bigger and more exciting.

I think the theater market, they need to maybe upgrade to sound and screens in a way that is something that they can't ever get at home, and whether that's more of a, you know, screen that wraps a little bit.

I don't know the technologies that the people are looking at, but bringing that experience up.

We'd probably be involved in investing in that with the theaters.

But making that experience, 'cause I think that 3D, it's gimmicky most times.

Not necessary to make a lotta movies 3D.

James Cameron's movie "Avatar," he knows how to do it right.

It wasn't deep 3D.

It was just the right amount, you know, of depth, so we're not really looking at that too much anymore, except for a couple of markets around the world we might do a 3D version 'cause that's what people only wanna see.

China, for one.

But, yeah, so I would say that where people see their films would be improving, and we're always looking at ways to, you know, make it a more exciting story.

- Experience.

Well, Jerry, I wanna thank you so much for joining me here on "doubleFEATURE."

I admire you as a person and how you just don't represent yourself and your family, you represent the best of the Walt Disney Company, and I think all of us in the film community are grateful for how you represent us, too.

And thank you, and I look forward to seeing you soon and hopefully bringing a new production to Rhode Island.

Thanks so much, Jer.

The Legacy of George T. Marshall

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 58s | Remembering the founder of Flickers, George T. Marshall. (44m 58s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 59s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, writer, and actor, Tom DeNucci. (44m 59s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 2s | Interview with Alex Berard. (45m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 59s | Steven Feinberg interviews First AD, Emma Barber. (44m 59s)

Interview with Chad Verdi Jr. and Paul Luba

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 31s | DoubleFeature shows films from around the world and takes viewers behind the scenes. (45m 31s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 41m 15s | DoubleFeature shows films from around the world and takes viewers behind the scenes. (41m 15s)

Interview with Angela Peri and Lisa Lobel

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 25s | Interview with Angela Peri and Lisa Lobel (45m 25s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 45s | Interview with Jerry Ketchem. (45m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 49m 15s | Steven Feinberg interviews award-winning filmmaker, Elyse Katz. (49m 15s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 44m 30s | Steven Feinberg interviews storyboard artist, Martin L. Mercer. (44m 30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 19s | Steven Feinberg interviews Providence Pictures' Gary Glassman. (45m 19s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 40m 24s | Steven Feinberg interviews producer Erika Hampson. (40m 24s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 41m 56s | Steven Feinberg interviews directer/producer Joe Johnston. (41m 56s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 45m 29s | Steven Feinberg interviews producer David Crockett. (45m 29s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 42m 44s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview the late film director, Douglas Trumbull. (42m 44s)

Henry Bronchtein Interview Pt. 3

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 15m 25s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, producer, and production manager Henry Bronchtein. (15m 25s)

Henry Bronchtein Interview Pt. 2

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 14m 51s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, producer, and production manager Henry Bronchtein. (14m 51s)

Henry Bronchtein Interview Pt. 1

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 15m 33s | Steven Feinberg interviews director, producer, and production manager Henry Bronchtein. (15m 33s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 37m 9s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview producer and writer, Roger Lyons. (37m 9s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 27m 31s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview filmmaker Dante Bellini. (27m 31s)

Katie Reaves and Jennifer Jolicoeur Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 27m 7s | Interview with filmmaker Katie Reaves & Athena’s Home Novelties Pres. Jennifer Jolicoeur. (27m 7s)

Dr. Thomas Zorabedian Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 27m 6s | Steven Feinberg interviews professor and video producer/writer, Dr. Thomas Zorabedian. (27m 6s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 47s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview picture editor Rob Schulbaum. (26m 47s)

Ron Bachman and Devin Karambelas Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 45s | Steven Feinberg interviews Ron Bachman and Devin Karambelas from WGBH in Boston. (26m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 15s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview filmmaker Eric Latek. (26m 15s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 51s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview host of Conducting Conversations, Mike Maino. (26m 51s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 6m 34s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview actress, producer, and screenwriter Marlyn Mason. (6m 34s)

Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 16m 5s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview author Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel. (16m 5s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 26m 51s | Steven Feinberg sits down to interview director Alexia Kosmidor. (26m 51s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

doubleFEATURE is a local public television program presented by Rhode Island PBS