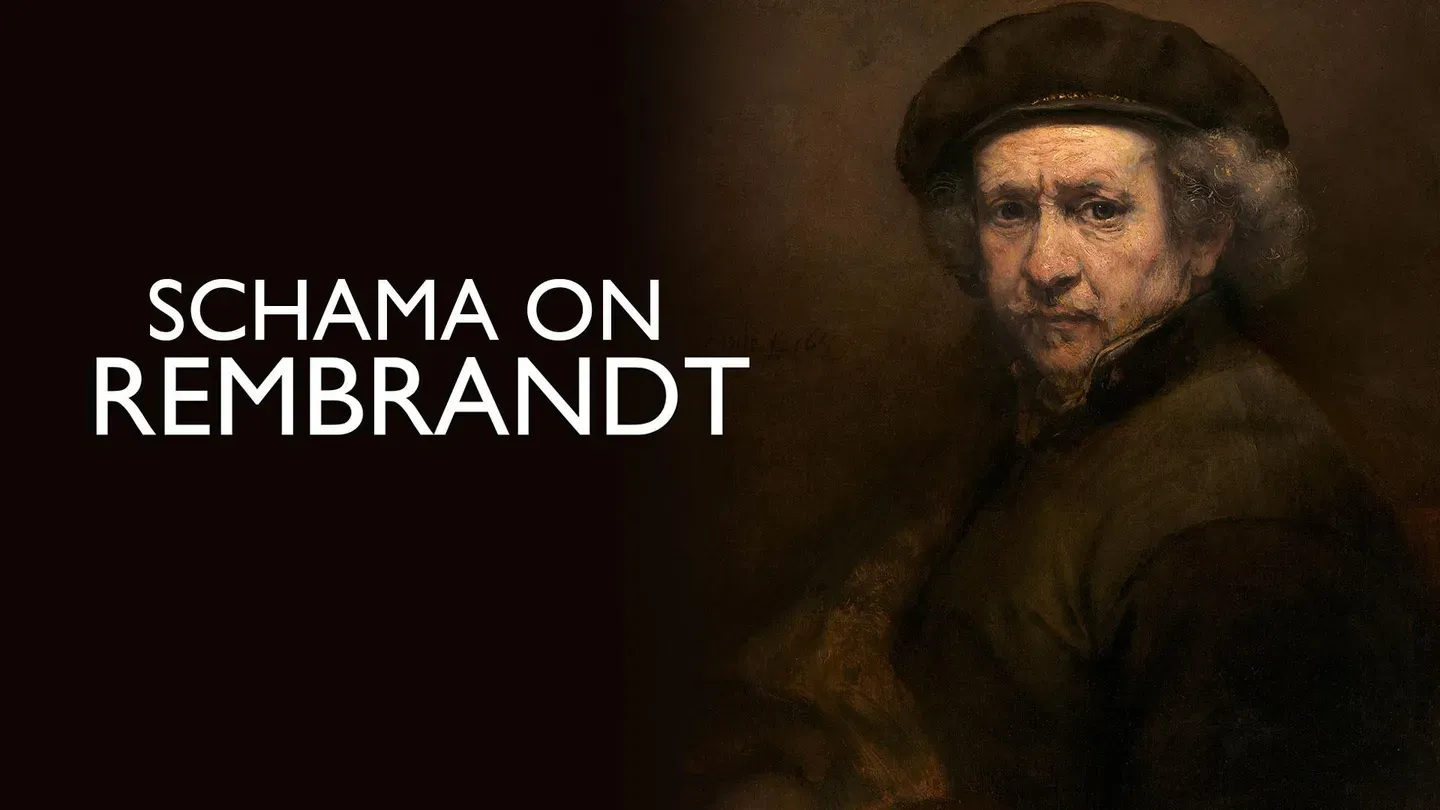

Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years

Special | 59m 29sVideo has Closed Captions

Simon Schama explores the final works of Rembrandt van Rijn prior to the artist’s death in 1669.

Historian Simon Schama explores the final works of Rembrandt van Rijn in the years leading up to the Dutch master’s death in 1669. Schama, one of the world’s leading experts on Rembrandt, details the creativity in these works as the artist found a whole new visual language to express the pleasures and pains of growing old.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years

Special | 59m 29sVideo has Closed Captions

Historian Simon Schama explores the final works of Rembrandt van Rijn in the years leading up to the Dutch master’s death in 1669. Schama, one of the world’s leading experts on Rembrandt, details the creativity in these works as the artist found a whole new visual language to express the pleasures and pains of growing old.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years

Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

-There comes a time when even the most self-absorbed artists look away from the mirror when they get old, vanity but gone.

Prepare for the end.

This was never going to happen to Rembrandt van Rijn.

Right to the last, he could no more do without the mirror than his brushes and paints.

But he tells it like he sees it, unsparing with the truth, every fold and wrinkle, bag, sag, and pouch relentlessly described.

And yet deep inside the ruin were all those other Rembrandts -- the precocious miller's son mugging for the mirror, the photo-booth clown trying out all the faces he'd need to give his painted stories passion, the up-and-comer talent-spotted by the great, in demand by all those who counted in Amsterdam... the master who's made it big in the richest city of the richest country in the world, preachers and princes, merchants and doctors lining up for him, the owner of a swanky house... the working artist, getting a bit of flak but just getting on with it, hearing voices of disgruntled patrons, critics.

Well, what did they know about art?

And then, as if to punish the proud, the face of misfortune... his wife dead... losses at sea and in trade, mortgage beyond him.

Rembrandt turfed out and into a small rental.

But he's not going quietly... not with a slow fade -- just the opposite.

The world which thought it knew Rembrandt hadn't seen anything yet.

♪♪ I think he saved the best for last, driven by the rage of age, going out like a meteor... thoughts and feeling welded together, masterpiece after masterpiece.

♪♪ He achieved things no one else had dreamt of before him and no one else could imagine until centuries have gone by, changing what painting could do, what art is.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Bell tolling ] ♪♪ The world had seen nothing like Amsterdam in its mid-17th-century glittering prime.

-♪ Vedro con mio diletto ♪ -There was nothing you couldn't get here.

The whole wide world was there for the taking -- rugs from Turkey, furs from Russia, spices from the Indies, porcelain from China, Spanish steel, and homemade beauties, too -- silver and glass.

-♪ Pien di contento ♪ -Money talked in Amsterdam.

Without it, you lost status, face, respect.

Rembrandt, who'd flown so high, learned this the hard way.

♪♪ In 1656, he lost everything he cared about in bankrupt ruin.

Even his house would go.

♪♪ The next 13 years of his life would be both testing and triumphant.

♪♪ ♪♪ So, it's -- it's a little, um, you know, kind of modest space, I suppose, by grandee standards but certainly not by Dutch standards, by Amsterdam standards.

♪♪ I mean, it's -- it is a grand room.

It is the reason why he couldn't pay the mortgage.

[ Chuckles softly ] 13,000 guilders is a lot of -- lot of money for an artist.

♪♪ So, up we go.

Ohh.

So, here's Mr. Shopaholic.

This is sort of a curiosity cabinet.

You can see there's sort of armor and plaster casts, essentially, so there is Socrates, for example, and, yes, there's the head.

That's got to be the Laocoon, the ultimate image of man in pain.

So, the rest of him would have been entangled in biting serpents.

But here we have, you know, birds of paradise, feathers.

There's a little caiman, crocodile, from South America.

There is an armadillo, is it not -- actually wonderful -- hanging.

I mean, who would have bought the armadillo?

I would, actually.

[ Laughing ] There's the answer.

[ Sniffs ] Ohh.

♪♪ With his bankruptcy, Rembrandt had lost something even more precious than his status.

He lost his art collection.

All of this -- the paintings, the drawings, his packrat collection of everything imaginable, all the props in the world, helmets, musical instruments, dressing-up costumes, stuffed animals, the whole kit and caboodle -- were knocked down at auction to settle debts.

♪♪ Now, somehow, he's got to carry all this around in his head.

But the challenge of this doesn't unman him.

He's not one to slink off into the shadows.

Instead, we get this.

♪♪ One thing about this extraordinary self-portrait -- it is the very personification of the authority of art itself.

♪♪ This is a painter who has been looking up at Titian and Rubens and van Dyck with a mixture of respect and ferocious competitive urge... ♪♪ ...at the same time, taking on what they would teach him and wanting to surpass them.

So he portrays himself.

Can you see this actually enthroned?

And the dress of art is, in fact, made of gold, so it can be mistaken for something that a king or a prince or a bishop would wear.

Something that you would possibly read as a maulstick, the extended stick which you stuck on the work surface in order to do detail, has turned into this nobly exquisite turned silver cane.

It's a baton.

It's the stick of authority, again, that you associate with palaces rather than the dump on the Rozengracht.

And it's frontal.

It's frontal.

Look how that belly swells out at you.

This looks kind of a hostile, confrontational torso.

From passage to passage of the painting, apart from the immense, authoritative, ferocious, broad-acred face staring right at you with that beret on top.

There is, of course, the issue of the vast, meaty hands -- the hands which are either going to create a masterpiece or they're going to strangle the critics, his huge hands, which, again, done with a maximum freedom, but the whole picture is a symphony of defiance.

"This is the way I paint," says Rembrandt.

"Love it or leave it."

♪♪ But plenty of the most desirable patrons in Amsterdam did just that.

They went elsewhere.

♪♪ Fashions were changing.

A new polished style from France was becoming the rage.

♪♪ What was wanted on their walls, including pictures of themselves, was brightness, color.

♪♪ For them, art was supposed to be all about refinement.

♪♪ Rembrandt was coming under attack from critics who held their noses at what they said was his coarseness, his undignified earthiness -- so much brown, such hideous models.

What does he think he's doing -- rubbing our noses in the ugliness of the world?

And what is this reckless, casual way with the brush -- all those dashed-off marks?

Maybe he's lost it.

Maybe in middle age, his drawing hand has become unsteady.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Kenwood House, Hamstead Heath, London.

♪♪ I first came here with my mom and dad in the 1950s -- a magic place, the fake bridge, the elegant Adam house -- and then, with girlfriends I was trying to impress, the outdoor concerts by the lake, lying in the long grass, composing a face I hoped would say, "I love Beethoven!"

when actually it was more like "Roll over, Beethoven."

It was here I saw my first Rembrandt that wasn't on a postcard or in a book, especially the little Skira pocket books I loved as a child.

Inside Kenwood, I came across this... ♪♪ ...and then, forever haunted by it, came again and again and again, usually by myself -- just him and me.

♪♪ I think because I'd seen in books pictures of the old Rembrandt, fluffy and puffy-faced, images of pathos, like most people, I thought of Rembrandt as essentially all heart.

But there was something else going on with this self-portrait.

That gaze is almost confrontational.

It's almost saying, "You think you know me, but here's what I really am."

It's a mighty head as well as a great heart.

It's about the mind.

Just remember, everyone, that what Rembrandt's being accused of as an old doffer is being kind of sentimental, sloppy, someone who can paint -- yes, he can do you big, heavy-hearted, expressive uses of paint -- but he can't really draw like the classical painters of the Renaissance.

That's what the fashionable word was -- "Boy, can he draw."

Rembrandt says, "I'll show you."

Those two half-circles that have produced shelves of PhD theses of what they might mean -- have been said, "Oh, one is the celestial globe, the heavens, one is the Earth."

Rembrandt knew about the Italian painter Giotto.

Giotto was summoned before the Pope and asked to do an instant painting, and what Vasari tells us Giotto did was the most impossible thing to do with a free hand.

He drew a perfect circle.

[ Men singing ] Rembrandt is saying, "You think I can't draw?

Here's your modern Dutch Giotto, if you like."

So there is an example of exactness in drawing.

But look at the hand.

Look at the hand where it's all supposed to be happening.

It is just a whir of motion.

People say, "Oh, well, it's an unfinished."

"It's not unfinished.

This is the hand that can be as precise or as expressive, as tight or as free as I want.

I'm the person who decides what's finished and what's not finished," and the rest of the painting is this extraordinary explosion of painterly freedom.

Yes, all the sense of feeling about a truly great artist under attack is actually there in this picture.

But most of all, it's a picture about the confidence of the marriage between head and heart.

♪♪ The idea that Rembrandt couldn't draw is absurd.

In his heyday, his reputation as a draftsman traveled all over Europe.

♪♪ Ah.

♪♪ So, this is very moving.

This is a room for etching.

Rembrandt loved the actual physical attack, whether he's painting or etching.

He's the ultimate dirty-hand artist, really.

This room would have smelled of acid.

[ Chuckles ] And, um... there's Christ Brought before the People, one of the late etchings, an incredible thing, and he's always having second thoughts, so there are many different states of the gray etching.

♪♪ This -- This one is Jupiter and Antiope.

Jupiter -- he's just staring obsessively at the darkened body of Antiope with the naughty bits in deep shadow.

♪♪ And it's very nice that the wonderful curators have put the so-called Three Trees out there.

What's fantastic about Rembrandt is the combo of dramatic effect and tiny little weenie touches of fine motor control, fastidiousness.

So, quite apart from this little drama of the gathering storm, which is going to pass because there's a brightness in the sky, on the horizon is Amsterdam -- indeed the kind of view Rembrandt would have had of Amsterdam when he walked into the country and up the Amstel, and there are figures in there, but there's just a tiny image of windmill sails you can see, and there are tiny little figures and details there which are just beautiful.

♪♪ Endearingly, there's even a version of himself happily at work.

♪♪ ♪♪ Rembrandt would often escape from the city and use his walks along the Amstel River as an inspiration for his etchings.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Cow moos ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Once Rembrandt had had his pick of patrons, but not quite so many now that fashions were changing.

He wasn't completely deserted, though.

There were those who gloried in being old-fashioned Hollanders, and some of them were very rich... none richer than the arms dealers, the Trip family, their wealth given substance in the biggest house in Amsterdam.

And portraits of Jacob and Margaretha, husband and wife, were commissioned to adorn it.

♪♪ What the Trips wanted in the midst of so much silky, high-colored vulgarity was something that shouted "old-fashioned virtue."

What they got was all that delivered in a storm of free painting.

♪♪ -Now, Rembrandt, old Rembrandt -- he can do old-fashioned.

He revels in being old-fashioned.

He may be almost revolutionary in the way he handles paints, but he's conscious that he is summoning the old-fashioned virtues of Dutch painting in its glory days earlier in the century.

Now, Jacob, the patriarch, actually is already dead when Rembrandt paints this, so Rembrandt would not have been able to do that one from life.

But, at any rate, it's kind of an idea in his head, and the idea is someone who looks like almost a biblical patriarch, who is venerable but loaded.

He's loaded with substance.

And often with Rembrandt, it's all about the props, and in this case, the prop is the fur collar draping the body and that fantastic silver cane, the cane of authority.

Next to him is Margaretha, the matriarch.

She comes from a family of enormous power, as well.

Copper, iron, you name it -- the de Geers, her family, have it.

And because Jacob is dead, Margaretha de Geer is allowed to look out directly at us.

If she was still alive and it was a marriage pair portrait, she'd have to incline her head just a little bit towards hubby.

Sorry.

That's -- Those were the rules.

But she's a widow, and the Dutch love fierce widows, so she doesn't have to do that.

She can look straight, actually, out at us.

Granny de Geer is flesh and blood.

And Rembrandt, the old Rembrandt, understands what time does to your face.

In her case, it sucks in the flesh.

It's -- It's so tight to the bone, you can almost see the skull underneath the cheeks, but he's not that brutal.

What he does very beautifully is have this sort of raw wind of the Dutch create a kind of rosy red tip of the nose and just on the edge of the cheekbone, and she's not going to wear any makeup to cover that up.

So the face has the sense of rosy, raw exposure to the Dutch weather, which already makes us real -- I think feel kind of sympathetic to her.

She, too, has fur around her.

She's also draped in the kind old-fashioned substance of her wealth.

But here, everything Rembrandt's done is about a dialogue of textiles -- the dialogue between that ruff, the bleached, starched millstone ruff, and that linen hanky she's clutching in the ropy-veined, mottled hand she has.

So it's the contrast here between the weight of the past, and the sense, actually -- There's a note, isn't there, of anxiety of the way she's holding this soft fabric of the linen hanky, 'cause husband's gone.

She is not going to be long for this world, as well.

Rembrandt knows exactly how she feels.

She's hanging on to that hanky for dear life.

♪♪ ♪♪ Patrons like the Trips who wanted old-fashioned were getting thin on the ground in Holland.

But if his star was dimming a little at home, it was still shining brightly abroad.

♪♪ [ Bell tolling ] ♪♪ Rembrandt was a bold-letter name in much of Europe and especially where you'd least expect it -- in Italy.

There were Italian patrons who wanted work by the Dutch master, and one of them was Don Antonio Ruffo of Messina in Sicily.

His palazzo was packed with portraits of the high-minded philosophers and poets, all advertising the don as a figure of taste and reflection.

Rembrandt?

Well, yes.

And this is what he produced.

♪♪ -There are actually three people in this painting.

The first one, of course, is the embodiment of the philosophical mind, weighed down as it is by wistful melancholy, as is the case for philosophers, at least in the classical writing about them.

The second one, Aristotle has his right hand on the lyrical pate, the beautiful poetic brain of Homer.

But there is a third person on whom the whole story, the narrative that he hoped Don Antonio Ruffo would recognize, depends, and that person is contained in a medal that hangs on the very end of the enormous golden chain that dominates the composition.

If you look hard, you will see that there is a little figure turned in profile.

The little figure -- you can just see his cute, not-very-classical nose, but above all, you can see the helmet, and the helmet would have told everybody this can only be Alexander the Great.

Now, the other two figures, Aristotle and Homer, both are connected in an interesting way to the figure of Alexander the Great.

Aristotle was Alexander's tutor when he was a child and prepared a new translation of The Iliad for the young, brilliant horse-rider and soldier to teach him the arts of war.

So, they are all connected by what was called in the 17th century a golden chain of being.

Both are honored in antiquity, I need hardly say, but both also come to sad ends -- Homer blind, despised, Aristotle also essentially sent into a kind of ignominious isolation.

So, in some sense or other, they represent for Rembrandt the complicated relationship between being acknowledged and being rejected.

And at the heart of it, weighing on the painting magnificently, as though he's kind of welded it to the surface, is that bloody great chain.

And if you go up to the painting closely, you will see Rembrandt, who was brilliant at doing metal all through his life -- he was definitely a heavy metal artist -- it's there in beads and buttons and gobs and knots and pools and blisters and warts of paint which stand out from the picture surface.

This is going to be the way he will operate.

So the chain is telling us something.

What's it telling us?

Well, when you were honored by a great patron, you were given a great chain of honor.

Rembrandt, ever since he was a kid, has been painting himself.

His fantasy is to have one of these fancy golden chains.

Does he ever get one?

No, he absolutely doesn't.

He's massively chainless for his entire life.

So, a chain will give you honor, but, of course, a chain also binds you like a prisoner to the whims of your patron, and Rembrandt, at this point, where he's been snubbed by the poets and the painters, all busy, you know, quaffing their malmsey, whatever they were quaffing, is saying, "Not me, busters!

Absolutely not!"

So this is a kind of manifesto, isn't it?

It's a manifesto of the thinking mind, the dashing hand, the poetic instinct.

There is a fourth person, I suppose, as there nearly always is in a Rembrandt painting, and it is obviously himself.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Don Antonio liked what he got well enough to order two more.

But Rembrandt took his time.

When he finally delivered in his later years, the patron felt as if he'd been slapped in the face.

The first one was Alexander and was painted on stitched-together bits of old paintings.

Oops.

And the second one... was this.

What you see now is terribly damaged by fire, but you get the idea.

And, as usual with Rembrandt, there was an idea behind the painting for which the style was meant to be perfectly suited -- Homer, thought of as the poet of the people, of lyric roughness.

Don Antonio was furious.

"This one is unfinished!

Take it back!"

This was more than a snit of egos and business.

At stake was a huge issue.

Who gets to say when a picture is finished?

♪♪ Refinement or rough poetry, the taste of the patron or the instinct and the intellect of the artist?

Would it prove to be the same old story when, in the last decade of his life, Rembrandt gets not one but two substantial commissions?

Either way, they were make-or-break jobs, the biggest you could hope for, and both featured men at a table.

♪♪ The first commission was a painting for Amsterdam's new town hall, built to rival any royal palace.

It was Amsterdam's answer to all the oversized architectural egos of kings.

Here, no grand entrance, immense rooms open to the public!

♪♪ The interior screamed "classical refinement" -- stony white spaces, marble floors, rows of tall windows.

♪♪ The burgomasters wanted to celebrate the heroism of their ancestry embodied in Claudius Civilis, the leader of a Dutch revolt against the Roman Empire.

But the Claudius Civilis they wanted to see was a figure of dignified nobility.

♪♪ Rembrandt wanted to do something completely different.

He was listening to a different kind of music, and that music was saying, "The Republic has gone soft.

If ever we were attacked, woe betide us because we're drowning in a kind of swamp of wretched luxury and excess."

So Rembrandt took the opportunity of this particular story to say, "Okay.

It's not that important that you're civilized.

It's incredibly important that you're free.

And this story, the story of your origins, the story of your ability to rebel against the tyrants of Rome, is all about the roughness of freedom.

You're going to get this, surely, because I'm going to paint you the roughest canvas about freedom in the roughest possible style you've ever seen."

♪♪ So he paints a hero with one eye in exactly the way you're not supposed to do.

You're not supposed to paint any hideous physical deformities.

That's what the classical rules say.

So Rembrandt starts with Claudius Civilis himself, his one non-eye staring straight out at the beholder, and the rest of the gang, the fellow conspirators, are this bunch of drunken ruffians, basically, in whom beats the breath of liberty and of freedom.

But this is, above all, an expressive one -- one almost wants to say an Expressionist painting.

Rembrandt paid the people who commissioned it and us, generation after generation, a huge compliment.

"It's rough," he says.

"It's rough because that way I'm pulling you into the action, into this immense flare of the light of freedom coming off the table, and you will finish the picture in your own imagination, in your own mind."

♪♪ But you will have to work twice as hard because what you're seeing is just a fragment of the immense original.

Rembrandt set his oath-swearing in a cavernous Biblical setting.

You'd have seen it like a sacred apparition.

Yes, this is a supper, but it's the first supper of liberty, the altarpiece to Republican freedoms.

♪♪ So, this was the nature of the gamble.

It turned into a catastrophe.

If he'd hoped the great and the grand of Amsterdam would get it, wow, they did not get it.

He had to take the painting back.

He had to cut it up in order to try and sell it.

He was never really paid, we think, a cent for all this effort.

But what we have is not just an imperishable masterpiece, not just a painting whose style is of a piece with its message, but maybe the first true work of modern art in the history of Western culture.

♪♪ He was down, but he was never to be counted out.

♪♪ There were still people who trusted him to deliver decent likenesses and -- Who knew?

-- something extra, too, a spirit of the group, maybe, even of the Drapers' Guild.

♪♪ Uh-oh.

Another bunch of men sitting around a table.

If Rembrandt was licking his wounds, though, over going right over the top with the Claudius Civilis, don't think for a moment that he's gonna go all quiet and respectful on us with this extraordinary painting.

I mean, think about this particular subject.

This lot of men are the quality-control inspectors of the Drapers' Guild having a meeting.

Fantastically exciting?

[Chuckling] No!

So he has to somehow dramatize it, as well.

He can't not bring some kind of energy into the composition.

So he turns the table 'round -- Doesn't he?

-- so that one corner projects out into our own space, so we're looking at the group, the entire group, including the standing figure, who's the live-in sort of civil servant of the organization, all facing us.

He's also paid some respect to their faces, which are so beautifully, if roughly, painted.

And that's very important that it's done sympathetically because this lot are different kinds of Christians, and yet they all hang together as the quality-control inspectors of the Drapers' Guild.

So we have black, white, black, white broken up by this great hot surge of magnificent crimson rug sitting on the table.

Look at the angle with which the table sticks out into our space.

Notice something?

It's the same angle as those men are looking out from the painting.

They're looking at something.

They're looking at someone.

Who exactly are they looking at?

Something else that's really interesting -- we know -- it's been suggested by a very clever art historian who noticed that the preparatory drawings are actually -- guess what -- drawn on account-book paper.

Yes, the same account paper as the ledger book we are looking at, which brings up the amazing possibility that what they're looking at inside the book is a set of drawings made by Rembrandt of the poses of the figures.

They're looking at the painting in the process of its own composition.

So, they're assuming the poses that Rembrandt's given them, which means they're looking at someone and they're looking at Rembrandt.

It's Rembrandt who's come into the room, but we are standing where Rembrandt is.

Rembrandt is us.

What a compliment.

♪♪ Rembrandt knew all about male bonding.

No painter ever had quite such a grip on its psychology, and no one came even close to understanding something else men do all the time -- look at women.

♪♪ Rembrandt was married for eight years to his first wife, Saskia, but she dies aged only 29.

He then takes up with his son's wet nurse, Geertje, but when she sues him for breach of engagement contract, he has her committed to a madhouse.

♪♪ In middle age, another servant in the house, Hendrickje Stoffels, becomes his common-law wife and gives birth to a daughter, Cornelia.

♪♪ It was this household -- Hendrickje, Cornelia, Titus, his son by Saskia, and Rembrandt himself who lived together in the Breestraat when his finances began to unravel.

♪♪ This is incredibly moving, really.

Whoa.

This is perfect morning light, and [Sighs] so it is sort of overwhelming, but you have this kind of opal pearl self-diffused light that falls on your working space.

This is ridiculous.

It's like sort of the great art director in the sky has sort of -- has said, "Fine.

You want a morning's work with Rembrandt?

Yeah, I can do the lighting for you."

So, he's done the lighting.

So, the light is falling on Rembrandt's easel, and it's really just unbelievably moving.

[ Sniffs ] That over there, the two palettes, one hung on top of each other, appear in the very first self-portrait when he's a very, very young man in Leiden.

He's a young man mantled in his working tabard, and his eyes are just two little black circles.

♪♪ Here are the pigments -- crushed lapis lazuli for aquamarine, famously very expensive, cinnabar for red, but then you suspend all these pigments in oil.

The oils are on the right.

It's also neat.

And linseed oil was a favorite.

I tried making pigments when I was writing "Rembrandt's Eyes" -- didn't work out very well -- 'cause, actually, I wanted to get the smell of it and I wanted to get the kind of sludgy texture.

I managed a few of them, but my paintings were sort of crap, but, actually, boy, you know, the smell of the painting -- My mother hated them being on the breakfast-room table, but I loved it, really.

Loved it.

So, this is very moving.

So, stretch -- stretcher frames, Dutch stove there.

What a beautiful working space, really.

♪♪ Um... oh, and here is Hendrickje with her shirt off.

This is so touching.

And one thing Rembrandt plays with all the time is he sees -- acting their role, he sees what our body language is.

So, he's taken -- He's unique in actually giving us our first image of what it was to model and still being actually who you are.

So, she's got a little hat on, and there are two objects on the table in front of her.

One is Rembrandt's drawing desk, slightly angled, and then there is the cart with the baby in.

So she's both model and she's mommy, as well.

She's nursing her baby.

So you have the complete world.

And then even in this kind of reproduction of that drawing, exactly the light I was just talking about -- it's just falling on this sort of perfect scene.

♪♪ Some of Rembrandt's loveliest paintings, warm with intimacy and sensual anticipation, came from looking at Hendrickje.

At the same time, he understood how ambiguous that looking could be.

The violation of modesty and how to paint it had long been an obsession of his.

In his prime, he'd already painted an astonishing picture in which we are turned into Peeping Toms.

♪♪ Now, the story is an apocryphal addition to the Book of Daniel, and it goes like this.

It's very simple.

It's that Susanna, virtuous wife, is spied on by a creepy bunch of elders.

They say, "Right.

If you don't sleep with us, we're going to accuse you of being an adulteress."

Bad, bad story, and it was used constantly as a kind of morality tale, but in a lot of Renaissance art, this is the most hypocritical moment, in which women's bodies, instead of actually being seen morally, were voluptuously turned for the convenience of soft-porn happiness of the patrons, over and over and over again.

Famously, images of Susanna -- and this is really creepy, everybody, there's no way around the story -- were used as aphrodisiacs for the elderly like me.

This is kind of visual Viagra.

When Rubens is hired, actually, to do a painting of Susanna and the elders, Dudley Carleton -- sorry, the British ambassador here in The Hague -- says, "Oh, it is going to be beautiful enough to arouse the appetites of an old codger like me."

Now, Rembrandt is no moralist, and he sure isn't a feminist.

The way he behaves with one particular woman certainly proves that.

But he has a staggering psychological grip.

The great sexual drama can be made out of telling the truth, out of, you know, turning the assumptions of what the nude is upside down.

This is not a nude.

This is a story about the observation of the naked.

Instead, actually, of the body being turned voluptuously towards us, it's all really about covering up.

This is a real woman with a real woman's body, and look at her.

She's looking directly at us.

In other words, we are implicated.

Whatever your age and whatever your gender, you, the viewer, are in a position of being a dirty old man.

There is a dirty old man hiding in the shrubbery on the right, so it's there, but, essentially, the drama depends on us feeling -- not kind of getting our jollies but actually feeling unbelievably embarrassed and awkward.

Rembrandt is incredibly interested in modesty.

So she takes what she can.

She grabs a piece of drapery and, in this complicated way, of course, covers up her groin.

And really kind of wonderful touch, absolute classic, brilliant gesture of the young and endlessly visually inventive Rembrandt, if you look at the sleeve of her dress, we sort of see what she was wearing when she was clothed that got them all excited.

So, the hanging-down sleeve almost echoes the arm that is doing the covering up, isn't it?

And with the other arm, with her left arm, it's pressed to her breast, so there's no titillation in any way at all.

This is a woman who's suddenly horrified at the kind of violation of the gaze.

♪♪ There are absolutely wonderful little details.

My favorite is that one of those feet is actually looking for and missing the slipper.

♪♪ So, it's a fantastic piece of drama -- not so much the embarrassment of being naked but the vulnerability of being naked.

♪♪ 20 years later, he would come back to the guilt and pleasure of looking, this time turning voyeurism into tragedy.

♪♪ The painting tells the story from the Bible of King David and Bathsheba.

Rembrandt joins together two episodes from the Scripture -- David spying on Bathsheba, the wife of one of his generals, bathing, and the moment when she receives a letter summoning her to the royal bed.

♪♪ Bathsheba is made a vessel of pure tragedy -- the lips on the verge of trembling.

Her gaze is both concentrated and distracted, the eyebrows tightly arched as though battling against the onset of tears.

Rembrandt makes us the ones doing the looking.

It's us who are accomplices, reeled into the web of desire.

An innocent act of bathing has been turned into a sinister moment of grooming.

♪♪ It gets even more complicated when you know that 1654, when it was painted, was also the year in which the model, Hendrickje, visibly pregnant, is hauled up before the church court for living in sin with the artist Rembrandt van Rijn.

Needless to say, poor Hendrickje shows up and gets this self-righteous earful.

Rembrandt doesn't bother.

Out of this personal drama fought over Hendrickje's body, Rembrandt produces one of the most psychologically complex nudes ever made, filled with passion and heartbreak.

♪♪ But it doesn't stop here.

♪♪ Four years later, he made this extraordinary etching -- not a nude but a model between takes, a woman feeling the cold and warming herself by a Dutch stove.

Real life has crashed into art.

♪♪ Rembrandt spotted another of art's little hypocrisies -- how paintings could assume the mask of outrage virtue while delivering the prurient thrill of sexual violence.

♪♪ ♪♪ Many artists had painted the rape of Lucretia and her suicide, told by historians of early Rome.

Here she is, the virtuous wife of one of Rome's consuls in its early days, ruled by the Tarquin kings.

The rapist is the son of the king.

Though she could not be more innocent, she can't live with the shame and commits suicide.

After the terrible deed is done, her family swear not just vengeance and justice but an end to the tyranny of kings.

♪♪ Some artists had painted the rape itself, where our eavesdropping and the full-on nudity repeats the violation while pretending to be horrified by it.

Rembrandt does things differently.

♪♪ It's an honor killing or an honor suicide.

I really don't know which is worse, but it's drenched in pathos and a sense of impending horror.

This amazing masterpiece is about the line between being dressed in the mantle of honor -- and just look at her.

You see how heavy that responsibility of the physical textile of the mantle of honor is.

On that Rembrandt has lavished his most immense dramatic powers of brushwork -- the relationship between that and the vulnerable nakedness of flesh.

We sense the presence of the brutalized, violated Lucretia's body from just the openings, the fastening at the top of the body.

But look, actually, at that composition.

It forms a kind of arrowhead, a "V." It moves down her body, emphasized by this heavy girdle, which is below her waist, not a place, actually, any dress in the 17th century I know of emphasizes -- of course, the site of her violation.

What is about to happen, inflicted by Lucretia, who's been crying -- Look at those -- Look at the pinked-up eyes.

Very rare.

You almost never see that in 17th-century or any other painting.

Look at the weight, the torrent of emotion that's waiting to pour out.

We don't just look at this painting.

We've heard her speak, possibly through a choke of sobs, about the demand to actually avenge this hideous crime by ending the corrupt kingdom of Rome and replacing it with a Republic of liberty.

So, we've listened to her.

This is the moment between the speech and the suicide.

Everything is in suspense.

So, the genius of the way he has actually executed this extraordinary moment of drama is to take us from this incredible crust of dark green paint to the single pearl drop at her throat.

This is the sign of chastity, of honor, of purity and the implication that beneath the whiteness, the perfect whiteness of that pearl, will come a traumatic effusion of blood.

♪♪ And then a bit later -- we don't know how much later, but perhaps 1666, three years before he dies -- he goes at the subject again, and this time, everything has changed.

♪♪ There are so many painted Lucretias, but never like this -- never with the blood pouring out of her.

She's dying fast.

Her face is a terrible sallow color.

The blood is on the dagger.

And suddenly we can feel two wounds -- the one made by the rapist and the one made in tragic desperation by the suicidal woman -- the depth and violence of both.

♪♪ And the blood -- no one has painted blood like this before, taken so much care with it.

This isn't prop blood, art blood, stage blood.

Rembrandt, the great thickener of pigment, has thinned it out, and he makes it dry, clot, then leak.

It's sticking to her shirt, which is stuck to her, and it's leeching her life away.

You just look, helpless.

She's dying alone.

♪♪ ♪♪ Rembrandt, too, at the end is quite alone.

There are some friends, the dwindling band of supporters, but except for his daughter, Cornelia, the family have all died, most heartbreakingly, one suspects, his son, Titus.

Titus' wife, Magdalena, Hendrickje -- it's just him now rattling around in the little house in the bad part of town.

So, towards the very end, he turns away from all those scenes of voyeurism, the estrangement of men and women, the sacrifice of torn bodies to something like its antidote -- the warm connection of family love.

♪♪ In October 1885, 220 years later, an aspiring young artist, one who spent much of his desperately lonely life searching for affection, would walk into the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, make a beeline for a particular painting, and stand there, eyes wide, heart pumping, sweaty with a fever of adoration.

♪♪ "I would gladly give 10 years of my life to stand before this painting for 10 days with only a dry crust of bread to eat."

What was it about The Jewish Bride that made Vincent van Gogh believe that the old Rembrandt had painted it, as he wrote, "with a hand of fire"?

♪♪ I think I know why van Gogh was so overwhelmed by this painting.

It does what every great masterpiece does.

It attacks us viscerally, and he was a very physical painter, and this, above all, is a painting about the physical embodiment of love.

It's a painting about what it means to be touched.

♪♪ At the heart of it is a play of hands -- a hand on a heart, which is also a hand on a breast, a hand touching that hand, the hand 'round the shoulder.

It is, above all, a play of hands testifying to trust, to confidence, to simplicity within the shelter of love.

♪♪ What this painting does is actually deliver more than it describes.

Let me give you an example.

The clothes, the outfit -- Rembrandt had a huge wardrobe full of costumes.

He loved dressing himself up, loved to dress everybody else up.

The paint is absolutely troweled on, and inside that paint, there is the entire world.

Bits of egg have been found in it, sand, silica, grit, earth.

He's kind of attacked the paint like a kind of feverish Modernist, like the great-great-granddaddy of Jackson Pollock or someone.

What you've got is this immense clotted, coagulated crust of colored paint.

That is the most physical thing you can possibly, possibly think of.

Now, it's probably painted -- we don't know the exact date -- around 1665.

Hendrickje has died in 1663.

This is not Hendrickje.

This is not a memory of Hendrickje.

But even though we're not allowed ever to be sentimental about Rembrandt -- he would not have liked that -- is it not possible, everybody, that if you want to retain the memory of what connects being physically touched with emotionally touched, you do it with massive, massive substance?

Underneath the mantling of all this paint is incredible tenderness.

Rembrandt is aware of mortality, of the perishability of life.

All great painting is about an attempt to stop time, to make memory physical, brilliantly colored.

What he wants to do with this particular vision of life is make it imperishable.

So if all of you out there worry about forgetting what it is like to be deliriously, confidently trustingly in love, stand in front of this.

This is the painting of love.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Support for PBS provided by:

Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television